Friday, July 31, 2009

Life in the gym

The story is based around Sugar Boy Younan who has been visiting Gleason's with his father since he was two and now, at the age of nine, is training for the Silver Gloves Nationals, Bantamweight division. As Lewin leads readers around the gym, following Sugar Boy and the people he encounters, he writes about the tip tap of jump roping, the buzz of the ring bell, the bam bam bam of the heavy bag slamming. There are "kickboxers from Thailand, girl boxers, big, burly wrestlers..." The gym is alive with activity and everybody - everybody - is welcome.

Hands get wrapped, shadow boxers line the wall, eyes turn towards the ring, everyone watches the sparring, everyone cheers. There are so many good things about how Lewin tells this story, the choice of language, the unconscious rhythm of the words, the overwhelming inclusiveness of the characters, that it's hard for me to point out one simple thing. I thought it was strong and beautiful, that it conveyed all the power of boxing and how that power can belong to anyone. Mostly though, it shows that Gleason's Gym is a place where anyone's dreams can be pursued. I can't think of a better ideal for someone to learn or a better book for a reader to learn on.

It's awesome.

Thursday, July 30, 2009

Oishinbo: Japanese Cuisine by Tetsu Kariya and Akira Hanasaki

Manga, like most western graphic storytelling forms, must overcome a preponderance of prejudices and stereotypes among American readers. In spite of (some might say because of) manga's success in American bookstores, the form is viewed as the exclusive territory of titles such as Naruto, Dragonball and OnePiece - male power fantasies with quirky (sometimes outright hallucinogenic) storytelling, frequent battles, and more speed lines than could ever be counted.

What a delight it is, then, when a manga publishing house as prominent as Viz Media decides to print something more than a little outside the norm, a title that seeks to educate more than titillate. That title is Oishinbo, and while it is new to America as of 2009, it has been published in Japan for over 25 years. There are literally hundreds of volumes and thousands upon thousands of pages in the Japanese Oishinbo catalogue, which no doubt created troubles for any company seeking to publish this work in America. Rather than meticulously translating, editing and reprinting each page from the very start of the Japanese series, Viz has opted for what they term the "A la Carte" approach - volumes compiled and heavily edited around a particular theme. Sometimes this approach works well, and other times it leaves a reader scratching his head. That is the price, I suppose, for attempting something ambitious and unique in the American manga market.

So, what is Oishinbo about? It's about food - specifically, Japanese cuisine - and the obsessions and aesthetics that drive Japan's culinary masters. But before you start thinking of this as nothing more than a heavily illustrated cookbook, you should also know that Oishinbo is about a young man and his relationship with his father, about the anger of youth and the cynicism of the aged, and about the quest for perfection. Don't expect any "Good Guys vs. Bad Guys" simplistic motifs. As is the case in real life, none of the characters in Oishinbo fits a neatly-designed cubicle.

The protagonist of the story, Yamaoka Shiro, is grumpy, pretentious, off-putting and occasionally brilliant. His background in the culinary arts, and his refined palate, have earned him the quest for the "Ultimate Menu," a lengthy newspaper assignment to assemble and create the most magnificent Japanese meal ever imagined. Shiro's antagonist is his father, Kaibara Yuzan. Yuzan is explosive, verbally abusive, passionate, and, like his son, utterly brilliant. There is much to like and to dislike about each of these men, and while the culinary lessons are intriguing, the human story of a rift between father and son is what lifts this work above its genre.

If it sounds as though I am gushing about Oishinbo, it's because I am. It's original, it's challenging, it's sublime - but it is not without its flaws. The main problem with this first volume lies primarily with Viz's decision to heavily edit this large work into discreet, bite-sized (no pun intended) chunks. While this first volume does a relatively good job of introducing some of the basics of Japanese cuisine (necessary knife skills, expected etiquette, and the tea ceremony, among others), it does so at the expense of character and conflict development. In culinary terms, Oishinbo: Japanese Cuisine is a pleasant and a somewhat unexpected appetizer, but if subsequent volumes follow the same pattern we will all be starving for a main course rather quickly.

Cross-posted at PastePotPete.

Wednesday, July 29, 2009

The Actor and the Text - and the Reader

But what about playing the opposite gender? How comfortable (or uncomfortable) would that be? How does the gender bending inform your voice, your speech pattern, your posture, your walk? What if you were portraying a historical figure attending the trials of Oscar Wilde? In 1895, Wilde, author of The Picture of Dorian Gray and many other well-regarded works, was brought to court, where his art and life were unfairly tried due to his sexual orientation.

As some of you know, I'm an actress. I've just been cast in a stage production of Gross Indecency: The Three Trials of Oscar Wilde. Written by Moisés Kaufman, the play is based on real events and uses actual court transcripts from Wilde's (in)famous trials. Kaufman is famous in his own right, known for his original plays and projects as well as his work as one of the members of The Tectonic Theater Project, the group behind The Laramie Project. Thus, the writing has a unique structure, almost reading/sounding like a documentary, with quick interjections of thoughts and quotes, clarified and underscored by various narrators.

I've played boys (or roles that are typically given boys) before. When I was a kid, I was Tiny Tim in Scrooge, a musical based on A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens. Every night, after curtain call, I'd take off my newsboy cap and let my hair fall down. That was fun, especially when I heard the gasp of someone who had been in the audience moments before.

The year before that, I fought for the right to audition for the role of Charlie in Charlie in the Chocolate Factory. They told me I couldn't, because I was a girl. I told them I could, because Charlie could be short for Charlotte, because girls could do anything boys could do, because I should at least be able to at least try. (Does it surprise you at all to learn I was this headstrong since I was, well, born?) Not only did I win the right to audition, but I won the role.

Back to Gross Indecency. I initially wanted to talk about the legal and social injustice that Wilde endured and compare that to similar persecutions and assumptions made today - but then I got an idea and thought I'd change it up a bit by discussing the actual storytelling of the piece.

Our interests in and reactions to stories might vary based on the genders of the characters - and also, in the case of written work then reinterpreted for the stage or screen, the casting.

Every time a play is performed, it is different. Each production is different, even when the dialogue is the same. The actors, directors, and others involved in the show collaborate on an interpretation and presentation of words which were previously strung together by a playwright.

When Gross Indecency first ran off-Broadway in 1997, the cast was made up of nine male actors playing multiple roles. My cast has the same number of people, but while men are playing Oscar Wilde, Lord Alfred Douglas, and the lawyers, women have been cast as the four narrators - one of whom also plays the judge. (Note that, as of this writing, we've only just had the first read-through. Blocking will begin later this week.) Will the presence of females change the story? The interpretation of the words? The audience's perception? Do you think an audience would react differently to an all-male cast, or an all-female cast?

Now think about this on a broader scale, and consider your own subconscious assumptions: When you read a play - or any printed story - in which a character's gender is not specified, do you picture a man or a woman? If that character speaks, do you hear a man's voice, or a woman's voice? Why do you picture the person - the gender - that you do? Does it depend on the reason the character entered the scene? The occupation or other nouns surrounding it? If it's a friendly neighbor, knocking on the door and sharing freshly-baked cookies, do you picture a man or a woman? If a one-line character is simply described as "a lawyer" or "a cop" or "a teacher" or "a doctor," do you picture a woman or a man?

Do you trust a female narrator more or less than a male? If a man writes a story from the first-person viewpoint of a woman, is that character and that story less valid than it would have been if a woman had written the story, or vice-versa? Along these lines, I could write another post entirely dedicated to the narrator of The Book Thief by Markus Zusak. If you haven't read that amazing novel, I won't spoil it for you here. I'll simply encourage you to pick up that book when you get up Gross Indecency, and read, read, read.

This discussion can go even further, asking what other character traits you envision, such as race or body type. When characters in books, scripts, and plays are "undescribed" or "under-described" (because those are two different things, mind you), do you mentally picture characters that resemble you or someone you know, or do you see John Does and Jane Does, purposely nondescript? It's much different than watching a film or television series, isn't it, if you can see and/or hear that character, when the pictures, sounds, and ideas are provided for you.

How much of what we take away from a story, any story, is based on our own experiences, perceptions, and interpretations? Don't we take away more than just the words of the writer? Don't we put a little piece of ourselves into that story, page by page?

Please feel free to discuss all of this in the comments below.

Oh - I failed to mention our director's gender. Did you notice this accidental omission, or are you only noticing now that I'm drawing your attention to it?

Monday, July 27, 2009

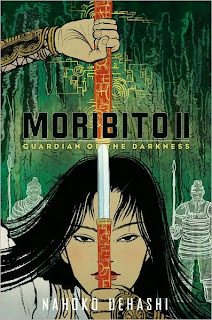

Moribito: Guardian of the Spirit and Guardian of the Darkness

Balsa is a bodyguard. She's been saving lives for years, but the challenges she faces in Guardian of the Spirit and Guardian of the Darkness, the first two novels in Nahoko Uehashi's Moribito series, may be her toughest ones yet. Her opponents now include the inhuman in addition to the human, and it will take more than guile and Balsa's mastery of the spear to defeat them.

Balsa is a bodyguard. She's been saving lives for years, but the challenges she faces in Guardian of the Spirit and Guardian of the Darkness, the first two novels in Nahoko Uehashi's Moribito series, may be her toughest ones yet. Her opponents now include the inhuman in addition to the human, and it will take more than guile and Balsa's mastery of the spear to defeat them. Set in a vividly depicted fantasy world, full of action and mystery and the supernatural, these two books are probably unlike most stories you've read. And they're very well-written, to boot.

Set in a vividly depicted fantasy world, full of action and mystery and the supernatural, these two books are probably unlike most stories you've read. And they're very well-written, to boot.In Guardian of the Spirit, Balsa becomes entangled with the destiny of the Second Prince of New Yogo when he is thrown from his carriage into a raging river. Balsa watches these events unfold, then jumps into the river to save his life. She does this with no expectation of rewards. She’s a bodyguard; saving lives is what she does.

But the Second Queen, the mother of Chagum, the Second Prince, begs her to take the Prince from Ninomiya Palace. The Second Queen fears that the Mikado, Chagum's own father, is trying to kill him, and Balsa is the only person the Second Queen can turn to to protect Chagum.

Guardian of the Darkness takes place directly after Guardian of the Spirit, as Balsa returns to her native land of Kanbal. She hasn't set foot in Kanbal since she was forced to flee the country as a child, but it is time, Balsa thinks, that she came to terms with her past. Except there are people in Kanbal who were under the impression that she was dead, powerful people with reason to think they would be better off if she really were dead.

After spawning anime and manga adaptations in Japan, the Moribito books are now being published in the United States. As the Publishers Weekly review of Guardian of the Darkness says, there's something for everyone here. Worldbuilding, imagination, intrigue, fight scenes, even awesome book designs. So if you're if you're looking for a change of pace or just want something good to read, give this series a try.

Friday, July 24, 2009

Men and Gods, by Rex Warner (illustrations by Edward Gorey)

You can hardly turn around, of course, without bumping into Greek mythology. From straight-up "re-imaginings" like the Percy Jackson books or God of War games to seemingly endless, more subtle references, the Greek myths are embedded deep in our cultural DNA--in movies, comics, literature, brand names, everywhere.

You can hardly turn around, of course, without bumping into Greek mythology. From straight-up "re-imaginings" like the Percy Jackson books or God of War games to seemingly endless, more subtle references, the Greek myths are embedded deep in our cultural DNA--in movies, comics, literature, brand names, everywhere. Fluffy in Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone? Obvious Cerberus homage. The tragic double-suicide at the end of Romeo and Juliet? Great idea, Shakespeare--except you totally stole it from the story of Pyramus and Thisbe. When someone has an Achilles' heel or an Oedipus complex? Takes on a Herculean task or opens Pandora's box? Greek myths are everywhere. (Even on your feet, if you're LeBron James.)

You can read some of the best--and, as if often the case, bloodiest--stories from Greek mythology in a very cool 1950s reprint that came out last year called Men and Gods: Myths and Legends of the Ancient Greeks. What's even better is that the book *looks* cool, a compact, hipster-edition hardback (still small enough to throw in a book bag) with simple, spooky illustrations on the cover by Edward Gorey, whom you might remember from macabre kids' books like the The Gashlycrumb Tinies and The Doubtful Guest.

The stories are retold in a spare, matter-of-fact style by novelist and classical translator Rex Warner that perfectly offsets the bleakness and capriciousness of many of the myths. Like, for example, here in a story about the Furies: "Meanwhile the terrible Tisiphone hurriedly seized hold of a torch that had been drenched in blood. She put on a dress, wet also with blood, and knotted round her waist a writhing snake. Then she left the lower world and with her went Grief and Terror and Madness with quivering lips"--and then the Tisiphone proceeds to dish out some ill-deserved "justice" to a couple of poor mortals via her snakes, "not biting them, but distilling their terrible poison into their minds." Then, as a hilarious little throwaway coda, Tisiphone "returned to Hell and undid the serpents which had girdled her dress."

These stories--37 in all, and many just a few pages long--cover many characters that you've probably heard of, or already even read about, like Hercules, Jason, and Perseus. But they also go deeper into the mythological bench, pulling up more obscure tales, like the one about how the beautiful Scylla ended up with snarling dogs for legs (after which you can feel confident using the old-school saying "between Scylla and Charybdis" instead of "between a rock and hard place").

Revenge and creative violence are sprinkled throughout, somehow always made better with Warner's unsentimental delivery. Like when Phineus was fighting Perseus because he stole away his fiancee Andromeda, "Now spears were thrown like rain through the hall, past eyes and ears, or cleaving through breastplates and thighs, or stomach." And when Pentheus offended the drunken god Bacchus, his female relatives were driven insane and--convinced by Bacchus' deception that Pentheus was a wild boar--tore him apart "with the strength of madness." They started with his arms, naturally, as was the custom in those days.

As is often the case with fables, many stories explain the origin behind some real-world phenomenon--like how Libya became both so snake-infested and dry (the former because Perseus accidentally dripped blood from Medusa's head while flying overhead, and the latter because Phaethon flew too close on an apocalyptic joyride with the nuclear chariot that he borrowed from his dad, the Sun).

On top of giving you an instant education in many Greek myths, Men and Gods is just a fun--and fast--read, easy to pick up and put down. To get a taste for the book, you can read one of the stories online, the story of Glaucus and Scylla, as a free pdf:

Thursday, July 23, 2009

The Selected Works of T.S. Spivet by Reif Larsen

Tecumseh Sparrow Spivet is 12 years old and a genius cartographer – two words you don’t often see together. T.S. is a master observer of the world around him. The boy “maps” his life, but these are usually not your ordinary, run-of-the-mill maps, like you use on a car trip or in the mall when you’re looking for the ice cream store. He maps his dad drinking whiskey, with a key for short sips and long sips; he maps how his mother met his father; he maps how to use your hands to play “Itsy Bitsy Spider”; he maps the evolution of the length of shorts from 1980-2007; he maps faces and hands and bones and the wings of cicadas. He also maps how the “patterns of cross-talk” dramatically changed around the family dinner table after his younger brother, Layton, died from a somewhat mysterious accidentally shooting. Lucky for us Larsen did not just write this book, he drew all of these maps, which fill the book throughout as marginalia. The drawings are worth the price of the book alone.

T.S. lives on his family’s Coppertop Ranch in Montana. His father is a Cowboy (with as big “c”) and his mother is a scientist. While T.S. is the creative intellectual of the family, wanting nothing to do with ranching, his brother Layton is the child–Cowboy, joined at the hip (or the horse) with their dad. But Layton is dead and T.S. and his dad hardly exchange a word. In fact, no one in the family ever mentions Layton, so T.S. writes (and draws) about his brother, and slowly, their family story emerges like a map of life.

T.S. is famous. At least in the world of science. For years he’s been doing drawings and maps for publications and more importantly, the Smithsonian Museum, which has given him a prestigious award. They have no idea he’s only twelve. Thinking he’s an adult -- you need to give Larsen a bit of literary license here -- they invite him to come to Washington and make a speech and work for a year. T.S. has never been to the east coast, is deeply enamored with the Smithsonian, and sees the offer as a perfect way to escape the pain of his family’s silence. So T.S. takes off. Hops a freight train and maps his journeys, both external and internal.

In some ways T.S. Spivet is a work of brilliant art. It can open your eyes to the wonders of observing the world around you, from an atom to a tree to a conversation to the solar system, as well as to science and history, and seeing (and drawing) connections from the past to the present, and how the world works. I loved this book -- but unfortunately, the freight train of my love started to hit the brakes about three-quarters into the book, and soon those brakes were slammed to an ear-piercing squeal as his story leaves the drama of his family and his inner journey, and enters some secret society at the Smithsonian and wormholes in the Midwest. You read that right. This is not a situation where I simply did not like the ending of a book. Larsen has vast talent, but he really needed to rethink the last quarter of his story.

Is it worth reading? Absolutely. Take this journey of maps and cross-country travel and be fascinated. Read it to the end, but ignore the end. Focus on how this character makes sense of the world by drawing it, and his passion for seeing and thinking and tinkering with a notebook and a pencil. Maybe when you go out to eat you will grab a napkin and draw a map of your own.

Tuesday, July 21, 2009

Woody Allen the Silly Existentialist

Let’s rewind a long, long way … back to the days when Allen was a young nutcase, a stand-up comic, a renegade movie-maker and one of the weirdest writers on the planet. You’ll find proof of this last assertion in his books “Without Feathers,” “Getting Even” and “Side Effects.” you can get them separately, but I’ve got mine in a single volume.

Here’s a sample that will not only give you the flavor of his work, but also explain the title of the first book:

“How wrong Emily Dickinson was! Hope is not 'the thing with feathers.' The thing with feathers turned out to be my nephew. I must take him to a specialist in Zurich.

Or try this “thought:”

Why does man kill? He kills for food. And not only for food: frequently there must be a beverage.

Allen was obviously a man in quest of intellectual input. He then outputted it in the form of mockery, absurdity and complete nonsense. Allen samples and remixes history, philosophy, poetry, college course descriptions, slang etymology, Melville, Milton, Noam Chomsky, ballet and, of course, religion.

Pieces include the letters of Vincent Van Gogh to his brother Theo -- if Vincent had been a dentist. Then there’s Death (A Play). Is this an existential masterpiece or a parody of one or both? It’s certainly more fun to read than Robbe-Grillet, I can tell you that much. Try this bit of business, when a mob thinks Kleinman is a killer:

John: “Let’s sting him up right now!”

Kleinman: “Don’t come near me! I don’t like string!”

What exactly will you gain by reading these books? Will you find them funny or more like a museum of what was once funny to previous generations? I can’t say, but I suggest you try it out.

Monday, July 20, 2009

The Uninvited by Tim Wynne-Jones

Throw together two potential stalkers, two burned out students, a famous artist and a Mini Cooper and you get The Uninvited by Tim Wynne-Jones.

Throw together two potential stalkers, two burned out students, a famous artist and a Mini Cooper and you get The Uninvited by Tim Wynne-Jones. Mimi Shapiro drives her Mini from New York City to a lonely cottage in Canada to relax for the summer, but finds it occupied. Jay, a struggling musician, is getting creeped out by the odd things he keeps finding in his cottage, when a girl shows up unannounced. Cramer is a townie who uses the waterways to see everything that goes on in his town. Meanwhile, Mimi's famous father remains in NYC, completely indifferent to what he has put into motion.

Jay and Mimi continue to use the serene cottage, but try to figure out who would sneak in to leave a dead bird, a snakeskin and other strange things. This is a really creepy book, but it is really much more than just a scary read. The characters and their relationships are all fleshed out which helps make the strange circumstances believable. Wynne-Jones provides perspective for each of the three narrators. At some points the characters are oddly indifferent to the strange and potential dangerous happenings, but otherwise this is an engrossing read.

Friday, July 17, 2009

Getting the Girl

Been looking for a mystery starring a grade 9 nerdy guy / wannabe P.I. who is pretty clueless with the ladies, loves cooking class and who is crazy enough to start investigating some of the coolest kids in school? Look no further than Susan Juby's Getting the Girl: A Guide to Private Investigation, Surveillance and Cookery. This book has a lot going on - a high-stakes mystery, some really funny moments, a sharp critique of high school social hierarchies, even a little cooking, which all combined, makes for a unique and entertaining reading experience.

Been looking for a mystery starring a grade 9 nerdy guy / wannabe P.I. who is pretty clueless with the ladies, loves cooking class and who is crazy enough to start investigating some of the coolest kids in school? Look no further than Susan Juby's Getting the Girl: A Guide to Private Investigation, Surveillance and Cookery. This book has a lot going on - a high-stakes mystery, some really funny moments, a sharp critique of high school social hierarchies, even a little cooking, which all combined, makes for a unique and entertaining reading experience.Sherman Mack just started high school and he definitely falls in the social category of "almost invisible." Sure, he has a couple of friends, and he isn't the biggest loser ever, but he is far beneath the notice of the real social players at Harewood Tech: the cool guys and their "Trophy Wives." Sherman has a thing for Dini Trioli (the tenth-grade goddess who humors his attentions), detective novels (recommended by his friend Vanessa) and cooking class. Sherman might wish his mom was a little older, a little less into burlesque dancing and a little more into cooking and cleaning, but all in all, things could be a lot worse. The only thing that Sherman really worries about is the infamous practice of "defiling" that goes on at Harewood Tech. Every so often, a girl's picture gets put up on all of the school bathroom mirrors with a D written next to it, and after this happens, she is completely cut out of every social group. That's after she is publicly shamed and her reputation is dragged through the mud to the point that school life becomes utterly miserable. Sherman is worried because he suspects that Dini might be next in line for defiling. He decides to go undercover to find out who is responsible and to save any more girls from this humiliating and cruel fate. Sherman discovers that detecting, like getting the girl of his dreams, is not as easy as it looks.

Why you'll like it? Sherman is a riot, without being a caricature. He bumbles around and makes mistakes and seems totally real. All of the other characters, even the ones who appear in only a few scenes, are just as well-drawn, so that you can imagine whole stories about them beyond the book. I especially liked Sherman's mentor Fred King, who loves cooking and gardening and is surprisingly cool if you can get past the comb over. Mrs. Samuels, Sherman's cooking teacher, is great too, always offering up wisdom about what it's like to work in the food industry. I think what appealed to me most in this book is the fact that Susan Juby has produced a book that communicates just how brutal the effects of high school cliques can be, except she has managed to make her book funny. It never feels like one of those serious reads about the trauma and pain of high school, but it will make you think just as much. I'm hoping it's a series, because I'd like to see what Sherman solves (and cooks) next.

Wednesday, July 15, 2009

Next week, I'm running a camp for 7 to 9 year old boys through the bookstore. It's called Booyah for Boys camp, and I'm hoping it will rock. I've broken the days up into themes, things like Space, Pirates, or Castles, and I've been reviewing material. Each day I hope to have some fun running around stuff (making maps and burying treasure on Pirate day, for instance) plus some crafts (make your own spaceship out of cardboard boxes!) and games, maybe even some storytelling. I'm reviewing material, sorting through my old resources, and I've come across some things that just make me yearn for what I no longer have and no longer can do... like play the Prince Valiant Storytelling Game. But before I get to that, let me tell you how awesome Prince Valiant is.

Hal Foster began the comic strip Prince Valiant back in the 30's, which is when 80% of all the best comic strips ever were created. Prince Valiant is unlike any other strip you've ever seen: full panels chock-a-block with lush details, more "narrated illustrations" than comics, because there were never any word balloons and the panel to panel transitions were more about capturing broad epic moments than any particular sequence of events.

The title character began as a young squire seeking glory and honor in King Arthur's court. eventually, over thousands of episodes, he grows into a knight, pursues his lady love, and has epic adventures that ranged across the globe. Hal Foster's illustrations are some of the best any comics page has ever seen, and he meticulously researched the visual aspects of every element that appeared in the strip. Simply gorgeous, awesome comics with great characters and a unique perspective, Prince Valiant sort of languished for several decades, in my opinion, as it hit the end of the century. Squished into the Sunday quarter page, falling victim to its complex and long internal continuity, the strip felt, honestly, dusty and irrelevant.

Not so anymore. A little under a decade ago, the great Gary Gianni, an illustrator and cartoonist who has drawn, among other things, some great Hellboy stories, took over the strip, and, along with the writer Mark Schultz (a phenomenal artist in his own right), has breathed new life into this classic of the comics page. Andrews McNeel publishers, who put out most of the syndicated comic strip collections these days, sensed a good thing and has released the first big chunck of the Gianni Schultz collaboration in a recent volume called Prince Valiant: Far from Camelot. This is fantastic, and returns the classic Prince Valiant character and epic storytelling to bookstore shelves where everybody can see.

And classic it is: Gianni has made it so easy to slip back into the strip, whether you've read a few strips or hundreds or thousands of Prince Valiant pages, you'll easily pick up on what's going on. Gianni's fabulous art easily withstands the enlarged, prominent arrangement on the page. I got it shortly after it came out last year, and couldn't put it down. Also, even though it's full color, the book is paperback and affordable.

Anyways, so looking at the book took me back to my late teens, when I'd become jaded about lots of things I'd loved when I was younger, including games. I was a big roleplayer, having cut my teeth on Top Secret, Villains and Vigilantes, and yes, Dungeons & Dragons. But after awhile, the games seemed to get bogged down in rules upon rules, with subsections and tables for every weapon, how they were held, if the character was a sorcerer, wizard, magician, glamourist, etc. etc. etc. They all seemed to fail at the basic reason for roleplaying: getting a group of friends together to tell awesome stories. So I just about gave up on RPGs.

Not long afterwards, I came across Prince Valiant: The Storytelling Game. This was unlike any game that was out at the time it was released: a slim, one-volume game that geared all it's mechanics to step out of the way of the storytelling. Filled with the fantastic art from the strips, it paired down character's statistics to just a few abilities and skills, easily modified for any situation, and substituted an intuitive, versatile "heads vs. tails" system for dice. Wow, was it graceful and elegant and exciting. I was desperate to play it; unfortunately, I never did because I moved away to college and never found anyone interested in playing it. Everyone I described it to was either uninterested in the setting ("Prince Valiant? What's that?") or thought it sounded too simplistic.

Fools. Eventually, I gave away or sold the rules. But now, I'm thinking about these boys. And how awesome that castle day is going to be. And how I can sit them around in a circle, and tell stories of glorious knights on epic quests. I'd love nothing better than to look each of them in the eye and say, "Now what, valiant knight of the realm--now what do you do?"

Unfortunately, the book is long out of print. But maybe I can hunt up a copy of those old rules in a few days. Or maybe, just maybe, they were elegant and memorable enough, I can recreate them on my own...

The Return of Conan

Hither came Conan, the Cimmerian, black-haired, sullen-eyed, sword in hand, a thief, a reaver, a slayer, with gigantic melancholies and gigantic mirth, to tread the jeweled thrones of the Earth under his sandalled feet.-- Robert E. Howard, "The Phoenix on the Sword"

Conan the Barbarian in one of those iconic characters--like Sherlock Holmes or Dorothy Gale--that people think they know without bothering to read the actual stories they appeared in. After years of imitations, parodies, and cheesy movies, the popular imagination has reduced Conan to a brain-dead killing machine with all the personality and finesse of a sledgehammer. Thankfully, there's a slow but steady push going on to change that skewed view of one of fantasy's most arresting characters.

Conan was created by Robert E. Howard, a pulp writer born in 1906 in Cross Plains, Texas. Growing up only a few decades after the final closing of the frontier, he was surrounded by people who had known the west when it was truly wild and lawless.

In a letter to fellow writer, August Derleth, Howard wrote...

San Antonio is full of old timers – old law officers, trail drivers, cattlemen, buffalo hunters and pioneers. No better place for a man to go who wants to get first hand information about the frontier. The lady who owned the rooms I rented, for instance, was an old pioneer woman who had lived on a ranch in the very thick of the “wire-cutting war” of Brown County; and on the street back of her house lived an old gentleman who went up the Chisholm in the ‘80’s, trapped in the Rockies, helped hunt down Sitting Bull, and was a sheriff in the wild days of western Kansas. I wish I had time and money to spend about a year looking up all these old timers in the state and getting their stories.

Despite his sword-and-sorcery setting, Conan embodies the spirit of the cowboy more than the Medieval knight. Like any frontiersman, he's tough as nails, but also smart and endlessly resourceful. Through his adventures, Conan picks up several languages, along with knowledge of woodscraft, military tactics, and other skills a wandering swordsman and fortune hunter needs.

When Howard calls Conan as a barbarian, he doesn't mean he's stupid. Actually, "barbarian" is pretty high praise from Howard, who carried a vague distrust of civilization his whole life. A strong theme throughout his writing is how civilization makes men weak, petty, and cruel. Conan, on the other hand, doesn't obey any authority except his own moral code. He's a dangerous enemy, and just as loyal a friend. He can gain and loose a king's ransom with hardly a shrug. He drinks and feasts and chases more than his share of tavern wenches, but his passion is for life itself and for adventure. He'd never chose those pleasures of civilization over the chance to see what lies beyond the next mountain. That's what Howard means when he describes Conan as a barbarian.

And what did lie over that next mountain? Often, something very large with lots of tentacles. In a recent GLW post, Jesse Karp described Howard's world-building as "massively atmospheric," and his Conan stories are set in a "vanished age" after the sinking of Atlantis and before the dawn of recorded history. Strange relics, ancient before the coming of men, pulse with vile magic. Forgotten gods lurk just outside the firelight, searching to recapture their lost glory.

The Cimmerian stood upright, trailing his sword, a sudden sick weariness assailing him. The glare of the sun on the snow cut his eyes like a knife, and the sky seemed shrunken and strangely apart. He turned away from the trampled expanse, where yellow-bearded warriors lay locked with red-bearded slayers in the embrace of death. A few steps he took, and the glare of the snow fields was suddenly dimmed. A rushing wave of blindness engulfed him, and he sank down into the snow, supporting himself on one mailed arm and seeking to shake the blindness out of his eyes as a lion might shake his mane.

A silvery laugh cut through his dizziness, and his sight slowly cleared. He looked up; there was a strangeness about all the landscape that he could not define--an unfamiliar tinge to the earth and sky. But he did not think long of this. Before him, swaying like a sapling in the wind, stood a woman. To his dazed eyes her body was like ivory, and, save for a light veil of gossamer, she was naked as the day. Her slender feet were whiter than the snow they spurned. She laughed down at the bewildered warrior with a laughter that was sweeter than the rippling of silvery fountains and poisonous with cruel mockery.

The beautiful creature goads Conan into chasing her, leading him deeper into the frozen wastes. Then...

Two gigantic figures rose up to bar his way. The scales of their mail were white with hoarfrost; their helmets and axes were covered with ice. Snow sprinkled their locks, in their beards were spikes of icicles, and their eyes were as cold as the lights that streamed above them.

"Brothers!" cried the girl, dancing between them. "Look who follows! I have brought you a man to slay! Take his heart, that we may lay it smoking on our father's board!"

Once again reminiscent of the frontier stories he grew up with, Howard presents a dangerous, untamed world where even the strongest man is barely more than an bug.

Conan's adventures were originally printed between 1932 and 1936 in Weird Tales. Howard dabbled in every genre the pulp magazines published--fantasy, horror, westerns, sports stories, and mysteries--but Conan quickly became his most popular character. Howard died tragically when he was 30. Soon after, the owners of his copyrights started making some questionable decisions concerning Conan and his other creations.

The market was glutted with new, ghostwritten Conan stories and novels. Even worse, other writers were allowed to "fix" Howard's original stories when they were gathered into paperback collections. And the less said about Arnold Schwarzenegger's muttering, meat-head take on Conan, the better. Once able to speak multiple languages, suddenly Conan could barely manage one. By the 90s, Conan had become a joke. The original stories--along with Howard's other work--fell out of print.

A few ardent fans kept the lamps lit, though. They maintained websites devoted to taking a serious look at both Howard's and other pulp writers' work. They kept enough interest alive that Del Rey finally republished the tales of Conan--restored to Howard's original vision of the character--in three illustrated volumes. They were popular enough for Del Rey to publish more of Howard's creations, including Kull, another fantasy hero considered a precursor to Conan, Solomon Kane, a Puritan who travels the world fighting demons, and Bran Mak Morn, the last Pictish king, fighting a doomed war against the Romans.

Dark Horse Comics published an Eisner-winning Conan series that finished its run last year. It was followed by a Kull mini-series and an upcoming mini-series featuring Thulsa Doom, an immortal sorcerer who's battled both Kull and Conan.

Also, there's a Conan MMORPG and another movie, directed by Marcus Nispel, slated to come out in 2010, which will hopefully be better than the two from the 80s. (And couldn't be much worse.)

And besides preserving Howard's work, many of the fans who grew up reading his work in the 60s and 70s became writers themselves. Historical novelist Scott Oden, who says his own writing is heavily influenced by Howard's, points out...

Howard's legacy to fantasy is as prominent as that of Tolkien. Together, the two created the modern genre: Tolkien with high fantasy and Howard with low fantasy, or sword-and-sorcery. The influence of his style of writing is evident in the pages of writers as diverse as George R. R. Martin, Joe Abercrombie, or Richard Morgan.

And through them, Conan lives on to capture the imaginations of another generation.

(I got a lot of help on this post from Rusty Burke, the editor of several collections of Howard's stories and letters, and Scott Oden. Thanks to both of them.)

Cross-posted on my blog.

Tuesday, July 14, 2009

77 Love Sonnets by Garrison Keillor

When I was 16, Helen Fleischman assigned me to memorize Shakespeare's Sonnet No. 29, 'When in disgrace with fortune and men's eyes, I all alone beweep my outcast state' for English class, and fifty years later, that poem is still in my head. Algebra got washed away, and geometry and most of biology, but those lines about the redemptive power of love in the face of shame are still here behind my eyeballs, more permanent than my own teeth. The sonnet is a durable good. These 77 of mine include sonnets of praise, some erotic, some lamentations, some street sonnets and a 12-sonnet cycle of months. If anything here offends, I beg your pardon. I come in peace, I depart in gratitude.

A sonnet is a particular form of poem. It consists of 14 lines. There are two exceedingly traditional forms - the Shakespearean sonnet and the Italianate or Petrarchan sonnet (which allows a bit more latitude in rhyme scheme). Both of those forms traditionally use something called iambic pentameter (ten syllables per line, organized into 5 iambic "feet" - taDUM taDUM taDUM taDUM taDUM). Over time, however, increasing flexibility in rhyme schemes and meters crept in. That said, most sonnets continue to consist of 14 lines, some sort of rhyme scheme (even if slant rhyme or near rhyme is used), and the presence of something called a volta or "turn", usually found somewhere around the ninth line of a sonnet, but sometimes not appearing until the final two lines.

Here is an example of one of Keillor's less erotic poems about a couple in love:

A Couple on the Street

by Garrison Keillor

Apparently they are a scandalous pair,

Strolling the main drag, not quite hand in hand,

The tall young woman and the dazed old man.

And old ladies turn like wounded birds and stare

And shake their great red wattles and curse

And young women smirk at this ludicrous romance--

But see how tenderly his eyes seek hers

And their elbows brush-- and, defiant, they hold hands

And dare to gaze at each other. She is avid

To be loved and love leaps up from them

As music sprang from Mozart, and they can have it

All, Don Giovanni and the Requiem.

"Fools!" the ladies cry. "It should not and cannot be!"

And they are right. But O the sweetness and the courtesy.

This particular poem uses slant rhyme, and follows this rhyme scheme: ABBACDCDEFEFGG.

Here, from page 65 of the volume, is a Shakespearean sonnet (ABABCDCDEFEFGG)entitled "The Anger of Women":

The anger of women pervades the rooms

Like a cold snap, and you wait for the thaw

To open the window and air out the anger fumes,

And then a right hook KA-POW to the jaw!

And she says three jagged things about you

And then it's over. She bursts into tears,

The storm spent, the sky turns sky-blue.

But a man's heart can hurt for many years.

I have found the anger of women unbearable.

And when my goddesses have cursed the day

They met me and said those terrible

Things, I folded my tent and stole away.

I yielded to their righteous dominion

And went off in search of another opinion.

There are sonnets that are sexy and sonnets that are funny; sonnets that are a bit dour and some that are divine. The book is, above all, proof of the flexibility and continued vitality of the sonnet. And even though it's pink, and even though it's by some guy who your parents or grandparents like from the land of Public Broadcasting, this is one book that's worth a look. Take a look at the poem entitled "Obama", perhaps. Or at the series of twelve poems, each named after a different month of the year. Or, well, look at "Room 704" if you don't believe me:

The tennis players volley on the bright green court.

Slipping and sliding to and fro while up above

Them, spread naked on a bed in room 704,

A young woman sings the aria of burning love--

Her lover's head between her legs, her feet on his back,

And she is singing for pleasure, while outside

The streets are cleaned, construction is on track,

The buses come on time and people board and ride

And she lies, eyes closed, hands holding his, and moans

As he addresses her with all deliberate passion.

And the clerks sort the mail into the correct zones

And all the ATM machines have sufficient cash in.

Good sir, don't stop. We each must do our duty.

Some drive the bus and others drive the beauty.

Monday, July 13, 2009

Yes, I Said Iron Crotch

Just the word “Shaolin” invokes thoughts of mystery—monks practicing their fighting and meditative arts on the side of a mountain, esoteric practices that lead to “iron” body parts…With its title & subtitle, American Shaolin: Flying Kicks, Buddhist Monks, and the Legend of Iron Crotch: An Odyssey in the New China, practically sells itself. Matthew Polly grew up as the kid who was picked on and tormented by bullies. He even had a list entitled Things That Are Wrong With Matt. While he dreamed of heading to China and studying with the monks of the Shaolin Temple (like on his favorite 1970s TV show, Kung Fu), it seemed like just a dream. While studying at Princeton, he realized he could make his dream a reality. He dropped out of school and got on a plane to China, determined to acquire a combination of martial arts prowess, spiritual enlightenment, and self-confidence.

Polly’s account of his 2-year stint in China is a fascinating read. If you come just for the martial arts, you won’t be disappointed—while it takes a while for him to be fully accepted by the Shaolin monks, he eventually represents them in tournaments and becomes the first American to be accepted as a disciple. There are amazing pictures of kung fu feats and descriptions of the training that can lead to having an iron stomach, fist, or yes, crotch. While these monks seem almost mythical, Polly gives us the reality of living in the Temple--personality quirks, routines, and the hard work that goes into making their kung fu look so effortless. Reading American Shaolin will also give you insight about what it’s like to live in China as it changes in the first part of this century. Many folks dismiss nonfiction when it comes to summer reading, but this is exactly the kind of summer book I like—one that transports me into a different place and describes both the big picture of life there and the day to day routine with detail, insight, and humor. Matthew Polly’s web site has more info on him, links to other articles he has written, The Iron Crotch blog, and some videos of the monks of Shaolin doing what they do best.

Friday, July 10, 2009

Fresh Lobster With a Side of Barbarian

Looking for a symbolic creature to take on as persona, one that will strike fear into the evil and corrupt? A bat or spider, perhaps? A shadow? How about a lobster? I went on and on about the pulps, comicdom’s gritty, hero-packed progenitors, a few months ago (here to be exact). I mentioned, among other things, Lobster Johnson, a character who originally appeared in the pages of Hellboy and, though he never actually existed in the time of the pulps (the 1920s-early 1940s), captures the spirit of that era and brand of adventure with more panache than anything since the originals.

Looking for a symbolic creature to take on as persona, one that will strike fear into the evil and corrupt? A bat or spider, perhaps? A shadow? How about a lobster? I went on and on about the pulps, comicdom’s gritty, hero-packed progenitors, a few months ago (here to be exact). I mentioned, among other things, Lobster Johnson, a character who originally appeared in the pages of Hellboy and, though he never actually existed in the time of the pulps (the 1920s-early 1940s), captures the spirit of that era and brand of adventure with more panache than anything since the originals.The homage is expanded with Lobster Johnson: the Satan Factory (by Sniegoski), a paperback adventure in prose made to read like a yarn lifted right out of an ancient, dog-eared original. In the interest of full disclosure, I must tell you that I have not read the whole book yet (it hits the bookstore shelves July 22nd). However, there is a generous 30 page preview at the Dark Horse website, and I have read that and I was so excited I couldn't hold back. We see Dr. Jonas Chapel's fall into the world of crime and the supernatural, and a chapter with a James Bond-style pre-credits sequence as the Lobster engages in combat with a distinctly unpleasant gorilla (this guy fights gorillas quite a bit, actually). So the stage is set for a clash between the mysterious crime fighter and the doctor gone wrong. I've read a lot of pulps in my day and, with its dark and moody settings and fast-paced action, rings with authenticity like the echoing roar of a .45.

Speaking of pulp characters, you couldn’t find a more quintessential example of the breed than Conan the Barbarian. From Robert E. Howard’s original, massively atmospheric adventures to Frank Frazetta’s latter day visuals drenched in menace and masculinity, sword and sorcery owes the character as a great a debt as it does the hobbits and Elves of J.R.R. Tolkien.

The adventures were never better re-interpreted than in Marvel’s original 1970’s Co

nan series which, of late, have been collected by Dark Horse in their the Chronicles of Conan series. Take Volume 7 (by Thomas and Buscema) for example. It’s packed with double-crossing sorcerers, wicked sword fights, voluptuous, fiery female companions (perhaps the very archetype of these: Red Sonja) and most importantly, the grim-eyed, iron-thewed, barbarian anti-hero with the indomitable will. Best moment in a collection of nine issues filled with good moments: a toss up between Conan’s underwater battle with an ancient, tentacled monstrosity right out of Lovecraft (Howard’s good pen pal, as it happened) and Conan’s escape after being tied down nearly naked to be gnawed on by an army of rats. Whatever your taste in barbarian action, this is the ideal book to top off your foray into the frenzied, sinister world of pulp.

nan series which, of late, have been collected by Dark Horse in their the Chronicles of Conan series. Take Volume 7 (by Thomas and Buscema) for example. It’s packed with double-crossing sorcerers, wicked sword fights, voluptuous, fiery female companions (perhaps the very archetype of these: Red Sonja) and most importantly, the grim-eyed, iron-thewed, barbarian anti-hero with the indomitable will. Best moment in a collection of nine issues filled with good moments: a toss up between Conan’s underwater battle with an ancient, tentacled monstrosity right out of Lovecraft (Howard’s good pen pal, as it happened) and Conan’s escape after being tied down nearly naked to be gnawed on by an army of rats. Whatever your taste in barbarian action, this is the ideal book to top off your foray into the frenzied, sinister world of pulp.Thursday, July 9, 2009

Surviving the Most Hostile Place on Earth

When I was in library school, I read a bunch of books for my juvenile and young adult literature classes. The one that impressed me the most was Shipwreck at the Bottom of the World: The Extraordinary True Story of Shackleton and the Endurance, by Jennifer Armstrong. Starting in 1915, Sir Ernest Henry Shackleton and his crew were stranded south of the Antarctic Circle for more than a year. They had no ship and no way to contact the outside world. All 28 men survived.

Jennifer Armstrong does a wonderful job, describing Antarctica, a continent that supports glaciers up to two miles in depth. There are winds close to 200 miles per hour and the temperature can sink to 100 degrees below zero Fahrenheit.

And she tells how the crew, including a stowaway, suffered, but persevered.

After their ship Endurance was crushed by the ice, "Shackleton announced his plan to the crew: they would march across the frozen sea with two of the three lifeboats to Paulet Island, 346 miles to the northwest. To the best of Shackleton's knowledge, there was a cache of stores in a hut on Paulet Island from a 1902 Swedish expedition. What they would do once they reached this destination was not specified: it was enough to have a goal... They would have to walk the whole way, hauling their gear and the two boats. The men knew they were doomed without the boats; eventually they would reach open water. They would need the boats, no matter how burdensome they were to drag over the ice...

"... there was much to get ready... While McNeish and McLeod began fitting the lifeboats onto sledges, the rest of the crew began sorting their equipment. The men were given a two-pound limit on personal gear, which allowed them to keep only the items that were essential for survival -- although the Boss did allow them to keep their diaries and their tobacco, and the doctors were allowed their medical supplies. In a dramatic gesture, Shackleton took his gold cigarette case and a handful of gold coins from his pocket and dropped them on the snow. Gold was useless for the task ahead...

"...the men hauling the Caird and the Docker (two large lifeboats) were sinking up to their knees in slush, and their boots were filling with seven pounds of freezing water with each step... in three days they covered only seven miles..."

The book is illustrated with pictures taken by the crew photographer. And Armstrong tells a little about what happened to the crew after they got back to England.

This is the most incredible adventure story imaginable. If you like it, you might also enjoy Marooned: The Strange but True Adventures of Alexander Selkirk, the Real Robinson Crusoe; and Revenge of the Whale: The True Story of the Whaleship Essex.

I'll post reviews, but I have to read them first!

Wednesday, July 8, 2009

Wednesday Comics

Cross-posted on PastePotPete.com

Hey! You Got Photo Documentary In My Graphic Novel!

I don't know how to explain this. There are books you read that pry open a whole world you never knew existed. I mean, you've heard of places like Afghanistan and Pakistan, you've heard of small villages lying in remote regions, you know organizations like Doctors Without Borders exist and you know what they do, and you might even know (or remember) some recent history about the Soviet invasion and war with Afghanistan in the 1980s... but somehow it doesn't all add up to a single picture of that time, or place, or experience until a book comes along and drops you into the deep end and your fully immersed.

In 1989, a young French photographer named Didier Lefèvre is asked by the organization Médecins Sans Frontières to help them document their efforts to provide medical care to Afghans living near the war front who are without doctors or resources. It's a grueling journey requiring the group to sneak across the border of Pakistan illegally, to get to the farthest outposts where medical offices can be set up and, for Lefèvre, to make his way home safely on his own. Years later he recounts his stories to his friend, the illustrator Emannuel Guibert, and together the create a trilogy of books that document the experience. Those books, bound as one, are The Photographer: Into War-Torn Afghanistan with Doctors Without Borders.

As explained in the afterword, the concept was for Guibert to illustrate the story surrounding Lefèvre's photos, turning the enterprise in an unusual, and richly rewarding, hybrid of a photo travelogue and a graphic novel. The mix of graphic elements at times can feel like an artists scrapbook - along the lines of photojournalists Peter Beard and Dan Eldon - or sometimes require several pages of illustration that calls to mind (literally at one point) Tintin comics both in landscape and style. It's like a documentary with the narrative flow of fiction.

And it's about war. And people trying to do good against all odds. People and animals die with regularity. The absurdities of human experience abound. There are moments of terror and moments of humor and moments of great beauty. It is as much about the person behind the camera as much as the people being documented in front of it and shows that, if anything, a photojournalist's life isn't as glamorous as some might believe.

I felt this way when I read Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis some years back. It wasn't that I didn't know something about Iran, it was all that I knew was through Western eyes and media. It had never occurred to me – nor could I imagine – what it would be like to grow up during the Iranian revolution of the late 70s and the overthrow of the Shaw. I had met many who had escaped Iran during that time, people uneasy with the coming reforms, and I knew their stories but not those of the ones who stayed. In The Photographer. Lefèvre and Guibert fill in some gaps about the Soviet conflict with Afghanistan in the same way, showing us what the Western (let's be fair, mainly American) world did not report. The borders were full of peasant villages, with Afghan troops on foot or with pack mule, facing Soviet helicopters and the last days of the big Soviet Cold War arsenal.

I seem to recall the American response to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan was to boycott the Olympics.

While The Photographer. doesn't necessarily add a great deal of information about the full nature of the conflict it does manage to put human faces on a small moment in the history of a part of the world still very much in our headlines. It's the sort of book that has to potential to open young minds and make them want to learn more about Afghanistan, about photojournalism, about Doctors Without Borders, and maybe why this part of the world continues to capture our attention.

Mentioned in this review:

The Photographer: Into War-Torn Afghanistan with Doctors Without Borders

by Didier Lefèvre

illustrated by Emannuel Guibert

First Second Books 2009

Persepolis

by Marjane Satrapi

Pantheon Books 2002

The Journey Is The Destination: The Journals of Dan Eldon

edited by Kathy Eldon

Chronicle Books 1997

Zara's Tales: Perilous Escapades in Equatorial Africa

by Peter H. Beard

Alfred Knopf 2004

The Adventures of Tintin books

by Herge

Tuesday, July 7, 2009

The Book Fair for Boys is a HUGE success!!

Think about that - we have made it possible for these boys to have books to read.

According to Eve, the point person at IOW, the most popular books are Harry Potter (some things just don't surprise me anymore), titles about war such as Andrew Mueller's I Wouldn't Start From Here and Jay Kopelman's From Baghdad Withe Love and books on the harsh truth of gang life such as Luis Rodriguez's Always Running. We will be running book reviews in the coming months on many of the books and I can't wait to see what the boys have to say.

For those of you who donated or spread the word, thank you so very much. Expect to hear from IOW in the near future as notes are being written to ever donor. And for future reference, we will be running a book fair in late November to again help this group of teenagers. Six hundred books is certainly a lot but for 2,500 boys it's just the tip of the iceberg. We have started to build a library and intend to continue the work.

An Apology and a Course Correction

Now, I've got nothing against any of those things. Not at all. I like caffeine as much as the next guy. I probably consume more caffeine than your average Red-Bull-addicted 15-year-old at the skate park (that's where you are, right? all the time? that's where the commercials say you are). But the reality--and I mean "real" reality, not the one invented by marketing companies--is far more complex and more subtle than that. There are, of course, many many more types of guys than are ever depicted by marketers. There are, for instance, guys who read books. If there weren't, I wouldn't be writing this right now, would I? And almost all those types of guys, but particularly the type who read books, can and do think differently about women than the marketers would have us believe.

What I want to say is I haven't given you, the GuysLitWire readers, the respect you deserve. I've imagined you too much the way they--the Madison Avenue types--have wanted me to imagine you. I've thought that guys wanted guy books and I figured guy books, particularly in fiction, included only stories about guys, stories that had guys, and never women or girls, as the main characters. So I've avoided recommending many good books that feature women or girls as the main characters, assuming, stupidly, that you wouldn't be interested. But of course you aren't Neanderthals.

I read somewhere that the reason Disney makes so many more "boy" movies than "girl" movies is that girls will go to see boy movies but boys won't go to see girl movies. "We don't like it. That's just the way it is," Disney executives say. But if you look at the girl movies that they make, it's no wonder guys aren't interested. They are nearly all about princesses. Even when the princesses are tough enough to disguise themselves as men and go into battle or ride alone into the dark woods to save dear old dad from a ten foot tall talking lion-bear hybrid thing and his army of tchotchkes, what the princesses really want is to put on a fancy dress and get married. It's not only guys who are put off by this. I'm sure there are plenty of girls who can't get into these movies either.

Fortunately, the world of literature is more varied than the world of Disney movies, and gives us many books with girls as the main characters, girls who are neither princesses nor fairies, nor, for that matter, the tormented little playthings of boy vampires. Here are some of those books, mostly fantasy and sci-fi, because that's what I know, but some non-fiction too, for good measure:

Sabriel, by Garth Nix--This is one of the coolest fantasy novels I've read in recent years. It's set in an alternative world where magic exists and is practiced, but only within a small area called the Old Kingdom. Outside of the Old Kingdom, things are pretty much as they are were here on Earth in the 1930s. All of the magic practiced in the old kingdom seems to have a bit of a dark edge to it and there are those who use magic to do the ultimate evil--raising and animating the dead. Sabriel's father's job is to guide these dead back to the land of the dead, where they belong. When her father is taken away to the land of the dead himself, Sabriel has to return from school to the Old Kingdom and take over the job without the proper training. Nix creates a strange and fully formed world with plenty of zombies, demons and ambulatory corpses, plus one seriously hard ass cat. Sabriel herself is thoughtful and cunning and tough. The novel is followed up by a two-part sequel: Lirael and Abhorsen. You can read my full review here.

Sabriel, by Garth Nix--This is one of the coolest fantasy novels I've read in recent years. It's set in an alternative world where magic exists and is practiced, but only within a small area called the Old Kingdom. Outside of the Old Kingdom, things are pretty much as they are were here on Earth in the 1930s. All of the magic practiced in the old kingdom seems to have a bit of a dark edge to it and there are those who use magic to do the ultimate evil--raising and animating the dead. Sabriel's father's job is to guide these dead back to the land of the dead, where they belong. When her father is taken away to the land of the dead himself, Sabriel has to return from school to the Old Kingdom and take over the job without the proper training. Nix creates a strange and fully formed world with plenty of zombies, demons and ambulatory corpses, plus one seriously hard ass cat. Sabriel herself is thoughtful and cunning and tough. The novel is followed up by a two-part sequel: Lirael and Abhorsen. You can read my full review here. His Dark Materials (The Golden Compass, The Subtle Knife, and The Amber Spyglass)by Phillip Pullman--Like Sabriel, this story is set in an alternate world, much like our own but different in important aspects. For one, people in this world have daemons, animal-like creatures which, while autonomous and separate, are linked to each person's soul. Lyra is an orphaned child who lives, with her daemon Pantalaimon, among academics at Oxford university. When she discovers who her father is and that he's experimenting with a substance called Dust which could allow him to open a gateway to another world, she finds herself in danger of being abducted by her father's enemies and escapes into a dazzlingly strange world full of witches, angels, and armored bears. A Google search will reveal how much has been written about these books. A number of organizations have recommended banning them. That should be reason enough to read them.

His Dark Materials (The Golden Compass, The Subtle Knife, and The Amber Spyglass)by Phillip Pullman--Like Sabriel, this story is set in an alternate world, much like our own but different in important aspects. For one, people in this world have daemons, animal-like creatures which, while autonomous and separate, are linked to each person's soul. Lyra is an orphaned child who lives, with her daemon Pantalaimon, among academics at Oxford university. When she discovers who her father is and that he's experimenting with a substance called Dust which could allow him to open a gateway to another world, she finds herself in danger of being abducted by her father's enemies and escapes into a dazzlingly strange world full of witches, angels, and armored bears. A Google search will reveal how much has been written about these books. A number of organizations have recommended banning them. That should be reason enough to read them. The Wee Free Men by Terry Pratchett--Tiffany Aching, it seems, would make a good witch, even though she comes from the Chalk, which isn't good land for growing witches. That's what a number of older and wiser witches seem to think, anyway, and they attempt to recruit her to their school. When her brother, Wendell, is abducted by an evil queen and carried off into Fairyland (which is quite a bit less pleasant than it sounds), she has no choice but to start her training early. Fortunately, she has the help of a host of tiny, badly-behaved blue men who amuse themselves by drinking heavily, stealing whatever they can, and picking fights with much larger creatures such as horses. These fellows need a lot of keeping in line, but are frightfully courageous and loyal. Tiffany is tough and as bull-headed as the Wee Free Men, but also considerate and generous. The book is one of the most hilarious I've ever read. Tiffany's story is continued in A Hat Full of Sky and Wintersmith. All of the books are part of the massive Discworld series, which will keep you reading for a long long time. From the Discworld series, I might also recommend Monstrous Regiment, about a girl who disguises herself as a man and joins the army (along with a troll, an "Igor," and a vampire) in order to find her brother who's been recruited but is far too sensitive to be a soldier. It's sort of like Mulan, only funnier and without the fancy dresses.

The Wee Free Men by Terry Pratchett--Tiffany Aching, it seems, would make a good witch, even though she comes from the Chalk, which isn't good land for growing witches. That's what a number of older and wiser witches seem to think, anyway, and they attempt to recruit her to their school. When her brother, Wendell, is abducted by an evil queen and carried off into Fairyland (which is quite a bit less pleasant than it sounds), she has no choice but to start her training early. Fortunately, she has the help of a host of tiny, badly-behaved blue men who amuse themselves by drinking heavily, stealing whatever they can, and picking fights with much larger creatures such as horses. These fellows need a lot of keeping in line, but are frightfully courageous and loyal. Tiffany is tough and as bull-headed as the Wee Free Men, but also considerate and generous. The book is one of the most hilarious I've ever read. Tiffany's story is continued in A Hat Full of Sky and Wintersmith. All of the books are part of the massive Discworld series, which will keep you reading for a long long time. From the Discworld series, I might also recommend Monstrous Regiment, about a girl who disguises herself as a man and joins the army (along with a troll, an "Igor," and a vampire) in order to find her brother who's been recruited but is far too sensitive to be a soldier. It's sort of like Mulan, only funnier and without the fancy dresses. A Wrinkle in Time, by Madeleine L'Engle--Meg Murray has a lot of problems at school. She has braces, can't manage her hair and people think she's strange and even stupid. But that's not the worst problem. Her father has disappeared. When she's offered, by three strange women--Mrs. Whatsit, Mrs. Which, and Mrs Who--a chance to set off on a journey to rescue her father, she takes it, bringing along her little brother, Charles Wallace, and her popular but wounded friend Calvin. They travel through space, time, and multiple dimensions and are eventually forced to confront true evil. This book is a classic and as such, many schools at one point decided to make it mandatory reading. I don't know if they still do. I hope not. Even if it is required, read it as if it weren't. (Don't let them mess up your life.) A Wrinkle in Time is much better to read all on your own, without being confronted by study questions or pop quizzes. A Wrinkle in Time kicks off a series called The Wrinkle in Time Quintet.

A Wrinkle in Time, by Madeleine L'Engle--Meg Murray has a lot of problems at school. She has braces, can't manage her hair and people think she's strange and even stupid. But that's not the worst problem. Her father has disappeared. When she's offered, by three strange women--Mrs. Whatsit, Mrs. Which, and Mrs Who--a chance to set off on a journey to rescue her father, she takes it, bringing along her little brother, Charles Wallace, and her popular but wounded friend Calvin. They travel through space, time, and multiple dimensions and are eventually forced to confront true evil. This book is a classic and as such, many schools at one point decided to make it mandatory reading. I don't know if they still do. I hope not. Even if it is required, read it as if it weren't. (Don't let them mess up your life.) A Wrinkle in Time is much better to read all on your own, without being confronted by study questions or pop quizzes. A Wrinkle in Time kicks off a series called The Wrinkle in Time Quintet. Swimming to Antarctica, by Lynn Cox--I've dabbled in athletics all my life. I was on age group and high school swim teams, track teams, cross country teams. I even did some bike racing as a kid. As an adult I run road races and the occasional triathlon. My butt has been decisively kicked by more women than I could possibly count. Still, while I knew there were lots of women who could beat me at pretty much any sport, I did not know, until I read Swimming to Antarctica, that there had ever been a woman who dominated a sport, who was better at her sport than any man in the world. By the time she was fifteen years old, Lynn Cox was. She held numerous world records in open water swimming and channel swimming. She could swim in water so cold it would literally kill a normal human being. Swimming to Antarctica is her story. It's told with grace and humility. It shows what a beautiful sport long distance swimming can be and confronts much of the sexism that a woman athlete of her caliber was forced to face. If you are a male athlete, whether you think you're the shit or not, you should read this book and be humbled.

Swimming to Antarctica, by Lynn Cox--I've dabbled in athletics all my life. I was on age group and high school swim teams, track teams, cross country teams. I even did some bike racing as a kid. As an adult I run road races and the occasional triathlon. My butt has been decisively kicked by more women than I could possibly count. Still, while I knew there were lots of women who could beat me at pretty much any sport, I did not know, until I read Swimming to Antarctica, that there had ever been a woman who dominated a sport, who was better at her sport than any man in the world. By the time she was fifteen years old, Lynn Cox was. She held numerous world records in open water swimming and channel swimming. She could swim in water so cold it would literally kill a normal human being. Swimming to Antarctica is her story. It's told with grace and humility. It shows what a beautiful sport long distance swimming can be and confronts much of the sexism that a woman athlete of her caliber was forced to face. If you are a male athlete, whether you think you're the shit or not, you should read this book and be humbled.Monday, July 6, 2009

A moveable feast: In the Heart of the Sea

A while back, I reviewed the newly-published Ray Bradbury screenplay for the 1956 film of Moby Dick here on Guys Lit Wire. The book Moby Dick is a recurring obsession; every few years I'll re-read it (yes, including the allegedly boring bits) and plow through stacks of critical commentary. This cycle of Ahabery was spurred by an interview I did with writer/comedian Mary Jo Pehl (Mystery Science Theater 3000), in which she spoke about Melville. In searching for new material, I discovered a book about the Essex, a ship sunk by a sperm whale in 1820, and the whalers' subsequent horrific ordeal. This event inspired Melville to write Moby Dick; he even met several of the survivors.

In the Heart of the Sea: The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex, by Nathaniel Philbrick, is based on two first-hand survivor accounts, one by first mate Owen Chase published shortly after the disaster, and one by cabin boy Thomas Nickerson, 19 at the time of the sinking. Nickerson's account did not surface until 1980, and having two distinct accounts to draw on helps Philbrick bring the characters and their struggles to vivid life.

It's not just a tale of a whale, it's a tale of a whole society, the Quaker-laced whaling fleet based on Nantucket Island. This brief, shining society, centered entirely on the deaths of whales half a world away, provided most of the oil needed to keep the world's lamps lit, and its machines greased. Philbrick doesn't apply modern morality to them, but instead shows us how their narrow world view caused the rise and fall of both the island itself, and the particular sailors from the Essex.

I won't sugarcoat it: there's cannibalism. But Philbrick does such a good job getting us into the heads of characters, their ultimate decision to eat what's available makes perfect, if ghastly, sense. He also provides context, using the results of a 1945 study on starvation at the University of Minnesota to explain the gradual physical and mental breakdowns.

This is neither a horror story, nor a "triumph of the human spirit" tale. Philbrick presents the story with a minimum of garnish, leaving the reader to draw their own conclusions. What is certain is that the fate of the Essex led directly to the composition of arguably the greatest American novel ever.

Read an interview with author Nathaniel Philbrick here.

Netflix a Discovery Channel documentary on the Essex here.

And finally, a cheery pop song about cannibalism: