I've been thinking a lot about race of late, and not because of the recent election, our president-to-be, or the significant way in which Barack Obama has brought front and center many of our still simmering concerns about racial divisions in this country.

No, it was this blog post about, of all things, the newest incarnation of Jack Kirby's New Gods which sparked my interest. In it, David Brothers imagines superhero Scott Free as the apotheosis of Afro Futurism, an African-American and African-Diaspora expression of technology, science fiction, and the future (to grossly generalize).

Eventually, I get from here to a "Star Wars"-ian slave epic and a history of North America so beautiful it will terrify you and break your heart. Come with me after the jump to see how...

So, after reading that article, I was struck by how easily I have overlooked black SF, a lit tradition that's long-in-the-tooth enough and broad enough to include W.E.B. DuBois and George Clinton, Bootsy Collins, and the entirety of P-Funk mythology. Seriously, it never occurred to me that African American lit has a huge science fiction vein. I remember when Walter Mosley's Blue Light came out a decade ago, I thought he'd gone off the deep end.

It never ceases to amaze me all the ways I can have my head up my ass when it comes to issues of race and gender.

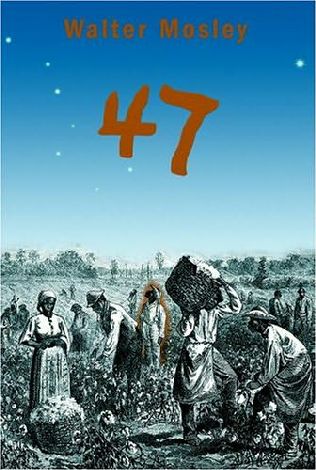

Anyways, I figured I'd rectify some of my ignorance by returning to Mosley, and picked up a copy of 47, his only venture into YA lit. The premise is this: an alien comes to earth, finds the one man destined to save the universe, and readies him for his fate. Only here, the destined savior is a slave in 1830's Georgia who is so stripped of identity he has no name, only the number 47.

First, before I go any further, if you've read any Walter Mosley, you know the taut, charged writing and full, burgeoning characters in his books. If not, this is a great place to begin. But here's the amazing thing: not only is this a great book that combines standard SF tropes with historical fiction, it turns inside-out some of the standards of science fiction. What happens when the evil empire of space opera is the slave-owning south, and the opressions inflicted by them are real, identifiable--even un-ignorable.

It strips away the safe distance discussions of the future can sometimes inhabit. You re-think nearly every SF book and movie you've ever encountered. Take Star Wars, for instance: what kinds of things was the Empire doing to maintain its stranglehold on all those planets. And not the antisceptic horrors onscreen, but the systematic, ongoing oppression of entire peoples. Stripping them of everything, even their names. Stripping them to the bone.

It's a slim volume, and ends before the epic part even takes off, but as a fresh look at history and a take on some of the old, worn out SF tropes, it really twists the knife. For an even slimmer, yet even more epic science fiction take on slavery, I pulled out a book I've been hanging on to for awhile but hadn't yet read: Terry Bisson's fantastic Fire on the Mountain.

Today is the anniversary of the 13th amendment, the one that abolished slavery. And I think, especially in the wake of our historic election, we have a tendency to think of racism as over, or at the very least, abated. Not racism on the small, individual scale, like racial slurs or even, God forbid, dramatic acts of violence. Not even the scale that we think of when we think big: restaurant chains refusing to hire or promote people because of their race, or, say, the visual impact of this political cartoon.

No, I'm talking racism on the largest of scales, scales that push us into places very, very uncomfortable to imagine. Places in imagination that force us to completely reimagine the world, possibly better or possibly worse, but stripped of some of our most venerated concepts and institutions if only to reduce the tremendous weight of something that infects, without us realizing it, how we define nearly everything around us, our institutions both public and private, even our very selves, whatever our race.

This is what SF, at its best, can do, though. Create ideas so powerful they make us tremble, and Fire on the Mountain is just such a book. Alternate histories have come into their own of late, but this one, over twenty years old by an unsung hero of SF, is about as phenomenal as alternate history speculative fiction can get.

Set in 1959, Fire on the Mountain opens on the eve of the second expedition to Mars, hyper-fuel efficient green technology cars and living matter shoes giving us glimpses of the utopian super-science at play in this very different world, a world radically different from our own in the most crucial sense of the word. This world made possible by a single event: the success of John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry in 1859.

In Bisson's alternate history, the ensuing century saw the rise of an entirely different America, indeed, an entirely different world: one in which the aforementioned amazing technological advances came not from this continent, but the continent of Africa--one in which global issues of poverty and conflict are much less prevalent. The tradeoff is nearly every institution Americans hold dear. There is no more United States, no Deep South, no Abraham Lincoln freeing of the slaves.

In Bisson's vision, John Brown's victory turned the Civil War into a slave revolt whose ultimate result is the establishment of an independent black nation called Nova Africa where the US South is today.

The great thing about all alternate histories is that they make our past more vivid, more real because we can see what was at stake in the choices that were made in the past. We understand just how fragile our notions of the inevitable can be. But the best alternate histories give us a vision of just how far we have to go to achieve our greatest hopes and dreams, even when we think our best historical moments are triumphs of the human spirit.

Hmm. I did go on a bit here. Rather than me blabbing on about this, instead check out these books:

47 by Walter Mosley is still widely available, but Terry Bisson's Fire on the Mountain is out of print. May I suggest one of these fine sources if your local library doesn't have it?

Also, if you're intrigued by Afrofuturism, which I barely touched upon, check out the anthology Dark Matter, edited by Sheree Thomas. It's fantastic, packed with lots of great short stories, including the aforementioned story by W.E.B. DuBois.

3 comments :

This is a GREAT post Justin! I've been thinking about reading 47 for awhile - I just didn't know enough about it to be sure if I wanted to give a go or not though. Now that I have your rec though, I'm all over it!

I know this is GUYS' Lit, but, but... Octavia Butler!

Walter Mosley can do no wrong.Fire on the Mountain sounds amazing, and I'm intrigued by some of the other authors mentioned. Thanks for an excellent summary!

(Octavia Butler!)

Well, I didn't even mention two huge YA releases this past fall: Chains by Laurie Halse Anderson and the sequel to Octavian Nothing by MT Anderson. Here are two looks at slavery at the inception of our country that are just fantastic.

(Octavia Butler, yes! And Samuel R. Delany, Nalo Hopkinson, Charles Saunders...)

Post a Comment