Tuesday, December 30, 2008

Into the cold

One interesting choice Farr made was to write the book from Cherry’s perspective. Relying primarily on Worst Journey for his text, Farr crafted a book that literally places the reader there with Cherry, Bill Wilson and Birdie Bowers as they struggled against enormous odds (and nearly died) in pursuit of the hidden secrets of bird evolution. While science has proven that Wilson’s thesis about the penguins was incorrect, the larger idea that birds and dinosaurs were related is true. But more amazingly, discovering that polar explorers actually risked their lives in pursuit of ornithological revelations is heartening in the best sort of way. They were brave and superhumanly determined and it was all for science. After so many books about winning it is wonderful to be reminded that Scott was in a race only because it was thrust upon him by circumstance; that his goal was always just to learn more. (Something that Richard Byrd and George Catlin would both understand.) Emperors of the Ice manages then to salute both men of adventure and intellect. There are action movies and video games and then there is what was accomplished at the bottom of the world nearly a century ago. This is thrilling writing and it will hopefully open up a whole world of polar literature to readers looking for something to believe in.

Cross-posted at Bookslut with review of other books for curious minds.

Monday, December 29, 2008

The Brimstone Network by Tom Sniegoski

Picture the X-Men, or the cast of Heroes. Now picture them younger, right when they are discovering and harnessing their powers, and you've got The Brimstone Network. It's an organization of warriors, sorcerers, and superpowered folks. Bram, a young teenager who is half-human, half-specter, inherited leadership of the group when his father, the original leader of the group, was killed in an attack that almost wiped their ranks out entirely. Now Bram not only has to find new recruits, he has to try to fill his father's shoes and keep the legacy alive.

The new and youthful members of The Brimstone Network have powers and abilities that fans of Heroes would love to have, like telekinesis and shapeshifting (psst . . . one of the main characters is a werewolf!) Some are tentative while others are tenacious. They must learn how to control and use their powers safely. Meanwhile, there are a number of villains who will stop at nothing to get what they want. For example, the second book introduces an evil vampire who can't be killed. Yikes.

If you are in the market for a new supernatural series for young readers, you've got to get this series. The Brimstone Network has lots of action and suspense, and it would be a really cool TV show or movie. I'm a sucker for stories with superpowers, and I really like how the different members of the Network struggle with their newfound abilities.

The first book in the line is simply called The Brimstone Network. The second book, The Shroud of A'Ranka, officially comes out tomorrow, December 30th, but it has already crept steathily into some stores. The third book, Specter Rising, will be released on January 27th. I can't wait to read it - and I really hope that Simon & Schuster lets the series continue!

In this series and others, Tom Sniegoski treats his young male protagonists very well. He lets them be boys, lets them be kids, even if they are in a hurry to grow up or have the weight of the world on their shoulders. His hilarious Owlboy series is for the same target audience as Brimstone, as is the magical OutCast quartet, which he wrote with Christopher Golden. There's also The Fallen, an angelic fantasy quartet which I highly recommend to teens and adults, plus his mystery novels for adults (A Kiss Before the Apocalypse, the forthcoming Dancing on the Head of a Pin) which feature Remy Chandler, an immortal, angelic private investigator.

For more information about the author and the series, visit www.sniegoski.com and www.sniegoski.com/brimstone I recently added a bunch of icons and wallpapers to the Brimstone site, thanks to the folks at Simon and Schuster, including illustrator Zachariah Howard and designer Karin Paprocki. Bram kind of looks like a young Indiana Jones on the second book cover, don't you think?

Friday, December 26, 2008

On Behalf of the Spirit

And while I've got you here, check out Will Eisner's original Spirit comics; there's about a zillion collected editions around now (but this one's a fine place to start). If Jack Kirby gave comic books their energy and power, then it was Eisner who gave them their unique form of expression. It's been said that he invented the language of the comic book the way Orson Welles defined the language of cinema with Citizen Kane. And you better believe that this is the only place you are ever going to see the Spirit movie and Citizen Kane mentioned in the same paragraph.

Addictive holiday reads

But that didn't stop me from packing what I hope are a couple of really fun books: 1) the graphic novel based on Prince of Persia (which David wrote about a couple months ago, and which I've been coveting as I've been contemplating getting PoP for my 360) and 2) Red Seas Under Red Skies, the sequel to the Lies of Locke Lamora.

When I was packing, I realized that's one of my personal holiday traditions (which I bet I share with many GLW readers): losing myself in a good book after the haze of food and presents and visiting--usually a fun, light book, and always something that keeps me turning the pages.

Here are a few of my favorite page-turners from past holidays:

- The Lies of Locke Lamora: This is fantasy, but it isn't Lord of the Rings. Locke Lamora is an orphan, an incredibly gifted grifter, and the leader of a gang called the Gentlemen Bastards. Think of it as "caper" fantasy--sort of like Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser crossed with Ocean's 11. I plowed through almost all 752 pages this Thanksgiving weekend! (Not surprisingly given its fast-moving plot, it's already being adapted as a movie.)

- Requiem for a Ruler of Worlds: This is a goofy, engaging space opera with highwire action and a Hitchhiker's Guide-style sense of humor (e.g., one of the protagonists' names is "Alacrity Fitzhugh"). The two follow-up books are equally worthwhile (Jinx on a Terran Inheritance and Fall of the White Ship Avatar), and this great author is also responsible for some equally page-turning fantasy and Han Solo stories.

- Fred Saberhagen's Book of Swords: I remember finishing this post-apocalyptic fantasy series over successive Christmas breaks in junior high and high school, and they're still some of my favorites. Saberhagen often starts with an ingenious "what if?" in his stories (much like in his famed SF Berserker series, with its self-replicating misanthropic robots), and the Book of Swords is no different. In this three-part series (with several "Lost Swords" follow-ups that'll have you combing through used-book stores), the gods have scattered twelve unique Swords of Power--with names like Coinspinner, Shieldbreaker, and Farslayer--across the world, as a game for mortals to fight over.

I'm obviously prejudiced towards SF and fantasy here, but if anybody else wants to share their ideas for good, light reads amidst the holiday daze, please add them in the comments!

Wednesday, December 24, 2008

Nexus - Best Comic Book Ever?

Here’s a Christmas treat for someone…

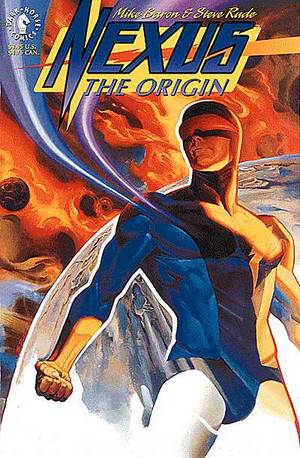

Nexus: The Origin, a fine comic book by Mike Baron and Steve Rude.

… to be given away to a deserving young reader.

Like Scrooge on Christmas morning, I throw open my shutter anxious to share the good things of life with others.

Now don’t get me wrong. This comic book -- or should I say graphic novella -- is not from my personal horde of Nexus comics. Heaven forefend!

However, I found it in a shoppe recently and thinking that it was a perfect introduction to the greatest superhero comic series ever written, I decided to scoop it up and make sure it got into deserving hands.

Yes, I’m giving it away to a lucky Guys Lit Wire reader. Keep reading for details…

What’s so great about Nexus?

It’s just one of those things where two great talents collide and create something more than a masterpiece, since after all any old master can make a masterpiece. This is rarer still.

The artist Steve Rude is simply astonishing. A designer of both pages and panels. An artist with wild new ideas and a love of old-school illustration. And a dude -- The Dude, he calls himself -- who is not above sneaking Kirk and Spock or something Seuss-ish into a book.

The writer Mike Baron is no slouch either, as they say. He’s got some big ideas and in Nexus he has found a way to turn them into a cracking good tale.

It’s a unique story among superheroes and Baron and Rude have found many ways to keep it taking new, surprising, even frustrating turns.

The hero, Horatio Hellpop, is tormented by dreams of mass murder. Dreams in which he feels the agony of every victim. The dreams don’t stop until he personally tracks down the killer and execute him.

To do this, Horatio has been given nearly infinite power. In most cases, the murderers stand no chance at all. In fact, in one of the finest stories, Horatio must kill a feeble old woman.

In this book, Nexus: The Origin, we see two of his first killings and two of the most interesting. In one we see Horatio -- now the all-powerful Nexus -- do some eye-ball popping, shazaam-tastic, comic-book blasting! But in the other, we see Nexus arrive to take down a horrible Nazi-ish figure. Like many of the Nazis, he’s no super-villain, just a bad, pudgy man.

Nexus come blazing in, like a million superheroes have done before. (Except drawn better.)

“Stand up and take it like a man!” he demands of his victim.

The man just cowers.

“NO? Then let your death be a little thing … quickly forgotten.”

He lays a finger on the man’s head. The murder is done.

And then the starving, tortured survivors crawl forth from the rubble. They need a place to go. Horatio decides to give them asylum, attempting to create a better society, but such a thing is never easy…

Once you’ve read this origin. You’ll be ready to plunge in. There are many issues of Nexus, several graphic novels and the occasional new book.

You’ll find many items at http://www.steverudeart.com/Comics_s/2.htm

or at TFAW, the amazon of awesome.

Otherwise, check your local comic shop or library.

One of our local libraries has a Nexus graphic novel in the Kiddie Comics section. Nope, this isn’t for kids.

If you’d like to get be the proud owner of Nexus: The Origin, send an email to sam@riddleburger.com with Nexus in the subject line and I’ll randomly pick a winner from all entries.

Tuesday, December 23, 2008

What It Is by Lynda Barry

Reviewed by Steven Wolk

Reviewed by Steven Wolk I post my reviews on the 25th of each month. This review spot in Guys Lit Wire--the 23rd of each month--is normally the place for Dewey's book review. Tragically, Dewey passed away recently. I was asked this month to post in Dewey's spot. I did not know Dewey, who was an English teacher (and that tells me something about her), but I want to acknowledge that this is her place. I'm just a guest today. Rest in peace.

There is just one Lynda Barry. Artist, playwright, novelist, comic creator. Lynda Barry is an original, and as my Grandma used to say, they made her and broke the mold. Her book, What It Is, is a visual and creative marvel. Nearly every page is a mixed media collage made up of found images, original painting, found text, added text, manipulated text, and photos. Barry puts them all together to create a beautiful and stimulating image on each page. You can spend hours looking at all of the details and reading the bits and pieces of text scattered around the pages.

Separately, the pages are a feast for the eyes, but together they are meant to motivate and inspire the artist and writer and thinker and creator inside each of us. Barry offers writing workshops, and this is a book version of her workshop. Most of the collage pages center around a question: What is the past made of? What are we doing when we are looking? Do memories have mass? Can images exist without thinking? Do you wish you could draw? What is intention?

What makes What It Is especially interesting--and gives it a vital dimension--is a running autobiographical narrative through the book. Barry relates key periods in her life that either hindered or energized her creativity. From her mother to her art teachers to her own self-doubt, Barry tells a compelling story that shows how easy it is for the people and systems around us to obstruct--or even destroy--our creativity, curiosity, wonder, and our youthful urge to create. In a nation (and a larger belief system of schooling) that does not value art, imagination, or questioning the status quo, What It Is serves as a bright beacon to nurture and appreciate the artist and thinker inside all of us.

I assume some readers will be compelled to just flip through this book to look at the amazing imagery and read an occasional piece of text. While there is nothing wrong with roaming through a book--in fact, this book makes marvelous meandering material--I urge readers to actually read the book. When you finish it you will feel the power and the joy of this wonderful thing called imagination.

Monday, December 22, 2008

Thaw by Monica M. Roe

Just one month ago, Dane Rafferty was the best skier on his high school skiing team. He was smart, dating a great girl, then all of a sudden, paralyzed by Guillain-Barre Syndrome. Dane has heard the doctors talking and knows there's a good chance he'll recover. Actually, forget the 75% chance the doctors are quoting—Dane truly believes he'll recover completely in just a month or two. After all, nothing has ever stopped him before.

Just one month ago, Dane Rafferty was the best skier on his high school skiing team. He was smart, dating a great girl, then all of a sudden, paralyzed by Guillain-Barre Syndrome. Dane has heard the doctors talking and knows there's a good chance he'll recover. Actually, forget the 75% chance the doctors are quoting—Dane truly believes he'll recover completely in just a month or two. After all, nothing has ever stopped him before.I'll be honest here: Dane is the most obnoxious, unlikable protagonist I've read about this year. He was also one of the most compelling characters I've read about this year. Maybe it sounds callous, saying I found a guy who used to be active and athletic but is now paralyzed to be obnoxious and unlikable. But, seriously, the guy's a jerk, and you can't blame the stress of falling ill or working hard in therapy for it. Most of the book is set in Florida, at the rehabilitation hospital Dane is convalescing at, but Roe devotes several chapters to Dane's pre-GBS life, and he was just as arrogant, selfish, and self-centered then as he is in Florida. (I'd actually prefer to call him something else, but I'm not sure it's allowed here at Guys Lit Wire.)

Liking a character and finding him compelling, caring about what happens to him in one way or another, are completely different things. Dane could be Exhibit A highlighting this difference. But I can't imagine Thaw working if Dane was depicted a nice guy. It would be too easy to pity him, to wish all of his problems would magically be resolved. As it is, Monica M. Roe has created a believably annoying, aggravating narrator in Dane, and the progress he makes—both physically and in terms of his personality—feel earned.

Thaw is a Cybils YA Fiction nominee and you can chalk this one up as another book I never would have picked up if it hadn't been nominated but am glad I read.

[cross-posted at The YA YA YAs]

Friday, December 19, 2008

Shift

Shift is every bookseller's dream because it is perfect for hand-selling. I mean, all you've got to say in your sales pitch is this: "So this story is about two friends who go on a bike trip across the country the summer before college and at the end of the summer, only one of the boys comes home. The other one disappears." Done. Sold. The customer is at the cash, money in hand, probably already reading the first page. Jennifer Bradbury sure came up with a premise that would make any author envious. What a great hook. I am happy to report that Shift lives up to the promise of its premise, one-hundred percent. Not only is this story a page-turner, it's a thought-provoking, nuanced read that touches on some pretty profound ideas about growing up, making your own way in the world and learning to let go. I've thought about the characters and the themes in Shift many times over the past weeks. This is a story that sneaks up on you and stays there.

Shift is every bookseller's dream because it is perfect for hand-selling. I mean, all you've got to say in your sales pitch is this: "So this story is about two friends who go on a bike trip across the country the summer before college and at the end of the summer, only one of the boys comes home. The other one disappears." Done. Sold. The customer is at the cash, money in hand, probably already reading the first page. Jennifer Bradbury sure came up with a premise that would make any author envious. What a great hook. I am happy to report that Shift lives up to the promise of its premise, one-hundred percent. Not only is this story a page-turner, it's a thought-provoking, nuanced read that touches on some pretty profound ideas about growing up, making your own way in the world and learning to let go. I've thought about the characters and the themes in Shift many times over the past weeks. This is a story that sneaks up on you and stays there.Stories about journeys just about always work for me. I wonder if it's that I enjoy thinking about how a character's physical journey inspires or mirrors his/her emotional growth. This is certainly the case in Shift. Chris and Win experience the challenges of a demanding physical undertaking and as they get through those experiences (flat tires, crazy winds, rain and more rain), they find out more about themselves. It's almost like the journey brings them to greater understanding of themselves and of their friendship.

I will not reveal much more about the plot than I've already written because part of the pleasure of the story is the element of mystery. I liked the tension Bradbury created from the start. You really wonder what has happened to Win (the friend who disappears), and you feel like Chris (the one who comes home) may have secrets. You don't really know who is reliable. That's part of what keeps you turning the pages. Of course, there's also the fact that Chris and Win's friendship is completely convincing - in the way that they banter and get on each other's nerves and know when to be supportive and when to just back off. The way that the narrative is structured with Chris remembering the events of the summer almost as flashbacks interspersed with his present experiences at university was a smart move since this jacks up the suspense. As we read Chris's memories of the summer, we're ever-aware of the fact that things "ended badly," so we're always on the look out for what when wrong, just waiting for the trip of a lifetime to turn sour. Aside from suspense, this structure also creates a feeling of poignancy, because readers know that the good times the boys enjoyed were bound to come to an end before they arrived at their destination. The early part of their trip really reads like a golden time.

I love that this book inspires you to think about how profoundly mysterious just about everyone is, even the people we think we really know. Everyone has secrets, and secrets usually inspire the choices individuals make about where they want to go, and who they want to be. Shift is about trying something wild and crazy without really thinking it through, and how this sort of bigger-than-life experience can make you know yourself in ways you could never predict.

Shift is such an accomplished piece of writing that it's hard to believe that it is a debut title. I guess that makes Jennifer Bradbury a born storyteller. Lucky for us, Jennifer is hard at work on more novels and has already sold 3 books to Atheneum. Good news indeed. Find out more about Jennifer in my recent interview with her at Shelf Elf and in Carter's October Interview with Jennifer right here at Guys Lit Wire. Shift belongs at the top of your To Be Read pile. You'll whiz through it and then you won't stop thinking about it. Maybe you'll be tempted to plan an escape of your own.

Thursday, December 18, 2008

Ever heard of Afrofuturism?

I've been thinking a lot about race of late, and not because of the recent election, our president-to-be, or the significant way in which Barack Obama has brought front and center many of our still simmering concerns about racial divisions in this country.

No, it was this blog post about, of all things, the newest incarnation of Jack Kirby's New Gods which sparked my interest. In it, David Brothers imagines superhero Scott Free as the apotheosis of Afro Futurism, an African-American and African-Diaspora expression of technology, science fiction, and the future (to grossly generalize).

Eventually, I get from here to a "Star Wars"-ian slave epic and a history of North America so beautiful it will terrify you and break your heart. Come with me after the jump to see how...

So, after reading that article, I was struck by how easily I have overlooked black SF, a lit tradition that's long-in-the-tooth enough and broad enough to include W.E.B. DuBois and George Clinton, Bootsy Collins, and the entirety of P-Funk mythology. Seriously, it never occurred to me that African American lit has a huge science fiction vein. I remember when Walter Mosley's Blue Light came out a decade ago, I thought he'd gone off the deep end.

It never ceases to amaze me all the ways I can have my head up my ass when it comes to issues of race and gender.

Anyways, I figured I'd rectify some of my ignorance by returning to Mosley, and picked up a copy of 47, his only venture into YA lit. The premise is this: an alien comes to earth, finds the one man destined to save the universe, and readies him for his fate. Only here, the destined savior is a slave in 1830's Georgia who is so stripped of identity he has no name, only the number 47.

First, before I go any further, if you've read any Walter Mosley, you know the taut, charged writing and full, burgeoning characters in his books. If not, this is a great place to begin. But here's the amazing thing: not only is this a great book that combines standard SF tropes with historical fiction, it turns inside-out some of the standards of science fiction. What happens when the evil empire of space opera is the slave-owning south, and the opressions inflicted by them are real, identifiable--even un-ignorable.

It strips away the safe distance discussions of the future can sometimes inhabit. You re-think nearly every SF book and movie you've ever encountered. Take Star Wars, for instance: what kinds of things was the Empire doing to maintain its stranglehold on all those planets. And not the antisceptic horrors onscreen, but the systematic, ongoing oppression of entire peoples. Stripping them of everything, even their names. Stripping them to the bone.

It's a slim volume, and ends before the epic part even takes off, but as a fresh look at history and a take on some of the old, worn out SF tropes, it really twists the knife. For an even slimmer, yet even more epic science fiction take on slavery, I pulled out a book I've been hanging on to for awhile but hadn't yet read: Terry Bisson's fantastic Fire on the Mountain.

Today is the anniversary of the 13th amendment, the one that abolished slavery. And I think, especially in the wake of our historic election, we have a tendency to think of racism as over, or at the very least, abated. Not racism on the small, individual scale, like racial slurs or even, God forbid, dramatic acts of violence. Not even the scale that we think of when we think big: restaurant chains refusing to hire or promote people because of their race, or, say, the visual impact of this political cartoon.

No, I'm talking racism on the largest of scales, scales that push us into places very, very uncomfortable to imagine. Places in imagination that force us to completely reimagine the world, possibly better or possibly worse, but stripped of some of our most venerated concepts and institutions if only to reduce the tremendous weight of something that infects, without us realizing it, how we define nearly everything around us, our institutions both public and private, even our very selves, whatever our race.

This is what SF, at its best, can do, though. Create ideas so powerful they make us tremble, and Fire on the Mountain is just such a book. Alternate histories have come into their own of late, but this one, over twenty years old by an unsung hero of SF, is about as phenomenal as alternate history speculative fiction can get.

Set in 1959, Fire on the Mountain opens on the eve of the second expedition to Mars, hyper-fuel efficient green technology cars and living matter shoes giving us glimpses of the utopian super-science at play in this very different world, a world radically different from our own in the most crucial sense of the word. This world made possible by a single event: the success of John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry in 1859.

In Bisson's alternate history, the ensuing century saw the rise of an entirely different America, indeed, an entirely different world: one in which the aforementioned amazing technological advances came not from this continent, but the continent of Africa--one in which global issues of poverty and conflict are much less prevalent. The tradeoff is nearly every institution Americans hold dear. There is no more United States, no Deep South, no Abraham Lincoln freeing of the slaves.

In Bisson's vision, John Brown's victory turned the Civil War into a slave revolt whose ultimate result is the establishment of an independent black nation called Nova Africa where the US South is today.

The great thing about all alternate histories is that they make our past more vivid, more real because we can see what was at stake in the choices that were made in the past. We understand just how fragile our notions of the inevitable can be. But the best alternate histories give us a vision of just how far we have to go to achieve our greatest hopes and dreams, even when we think our best historical moments are triumphs of the human spirit.

Hmm. I did go on a bit here. Rather than me blabbing on about this, instead check out these books:

47 by Walter Mosley is still widely available, but Terry Bisson's Fire on the Mountain is out of print. May I suggest one of these fine sources if your local library doesn't have it?

Also, if you're intrigued by Afrofuturism, which I barely touched upon, check out the anthology Dark Matter, edited by Sheree Thomas. It's fantastic, packed with lots of great short stories, including the aforementioned story by W.E.B. DuBois.

Wednesday, December 17, 2008

Some recommendations

"The Best of Lucius Shepard and The Best of Michael Swanwick – I’m double dipping here, I know, but these two reprint collections are by two of SF/F’s best ever short fiction writers. From genre defining to genre breaking works and beyond, the reader is treated to continually great fiction. These are those kinds of books that if you don’t acquire them now, some day you’ll wish you had."

Both of those collections are from Subterranean Press, one of the best publishers in the business and particularly excellent when it comes to fantasy.

Some of you may recall thirteen-year old Max Leone's comments to PW about books guys want to read which we linked to here last month. (He was especially interested in a book about vampires that wasn't also about vampire romance.) (You do remember when vampires were something scary, right?) Max had a guest post last week at The Swivet where he gave some "holiday book recommendations for the teenage boy in your life". He has nonfic, manga, John Twelve Hawks and Terry Pratchett which is pretty much as eclectic as it gets. Here's my favorite of his reviews:

"SMARTBOMB: The QUEST for ART, ENTERTAINMENT, and BIG BUCKS in the VIDEOGAME REVOLUTION by HEATHER CHAPLIN and AARON RUBY (Copied more or less word-for-word from the book cover. It looked much less ridiculous there): Though the title alone makes it illegal to bring this book onto an airplane nowadays, it is another book that will be re-read countless times, as proved by my copy looking like a walrus sat on it. For several hours. Anyway, it features great information on the history of videogames. Recommended for gamers and non-gamers alike."

A lot of rage, a lot of machines

Heavy metal hit Egypt during the 90s. It started as a loose network of friends trading Black Sabbath and Metallica tapes smuggled in from the West, but within a few years, home-grown bands were playing for a burgeoning scene centered around Alexandria and Cairo's Heliopolis district.

Heavy metal hit Egypt during the 90s. It started as a loose network of friends trading Black Sabbath and Metallica tapes smuggled in from the West, but within a few years, home-grown bands were playing for a burgeoning scene centered around Alexandria and Cairo's Heliopolis district.Then, in 1997, the scene had grown too large for the powers that be to ignore. The strange, long-haired kids found themselves caught between religious leaders always on alert for moral corruption, a government terrified of any signs of dissent, and newspapers searching for the next scandal.

In Mark LeVine's Heavy Metal Islam: Rock, Resistance, and the Struggle for the Soul of Islam, Hossam El-Hamalaway, a metalhead old enough to remember those days, recounts, "All of a sudden I was seeing pictures in the newspapers of my friends, with captions under them describing them as the 'high council of Satan worship.' It was all quite frightening." The crackdown resulted in over a hundred arrests of musicians and fans, some as young a thirteen. More were simply attacked and beaten in the streets by the Mukhabarat, the secret police.

A decade later, plain clothes Mukhabarat agents still come to rock shows, snapping pictures of the bands and people in the audience. And there's still a pervasive sense of paranoia in Egypt's metal scene. The musicians LeVine spoke to were initially afraid to give a stranger tapes of their music or written copies of their lyrics, and most asked him not to use their real names in his book.

But LeVine spoke their language. Both literally--he's a professor of Middle Eastern studies who knows Arabic, Turkish, and Persian--and also in sense that he's a fellow musician who has played with Mick Jagger and Doctor John. Able to win the trust of musicians across the Middle East and North Africa, LeVine explored rock scenes festering below the surface of the most oppressive regimes in the Islamic world. In Heavy Metal Islam he writes about the harassment and frequent arrests they face, and tries to answer why, despite it all, these scenes continue to grow, attracting new fans and bands risking everything to get their music heard.

LeVine writes about Subliminal, a pro-Zionist Israeli rapper and also the mahajababes, young Islamic hipsters who combine their traditional veil (called a mahajabab) with Hamas jewelry and designer jeans, but his focus and heart are with the drop-outs--the "metaliens" as the call themselves--who use music to carve out small private spaces within a culture that often regards individualism as treason.

The lengths his metaliens go to are astonishing: secret shows, music recorded in underground studios and distributed across the internet. Almost none of the musicians LeVine interviews are able to make a living with their music; many have never even told their parents they play music. Why do they keep at it? Reda Zine, a founder of the Moroccan metal scene, explains simply, "We play heavy metal because our lives are heavy metal."

A musical genre that emerged crumbling working class communities in England and America during the late 70s, heavy metal has always been the soundtrack of the young, angry, and dispossessed, words that could describe most of the population in places like Iran. LeVine writes:

Iran's mullahs have legitimate reasons to fear metal: it reflects the mood of a young generation (65 percent of the country's population) roiled by drug use, prostitution, increasing AIDS, and, most important, a nearly complete rejection of the values of the [previous generation's] Cultural Revolution.

Iran's mullahs have legitimate reasons to fear metal: it reflects the mood of a young generation (65 percent of the country's population) roiled by drug use, prostitution, increasing AIDS, and, most important, a nearly complete rejection of the values of the [previous generation's] Cultural Revolution. Perhaps the best indication of how strongly the country's metal community--and, by extension, a large share of the rest of Iran's younger generation--oppose the ethos of the Revolution comes from the popularity of pioneering British metal band Iron Maiden... The images of war's violence and futility--particularly as embodied by the band's mascot, the skeleton-monster robot Freddy [actually Eddie], blundering across the stage pretending to shoot the crowd--served as the perfect rebuttal to Khomeini's valorization of war and martyrdom as the holiest acts within Islam.

As Ali pointed out afterward, "There are so many images of war and guns on the streets and buildings of Tehran, it's the same symbolism really," Except that the Revolution's martyrs died "in the path of God," while Iron Maiden's die for nothing.

As Ali pointed out afterward, "There are so many images of war and guns on the streets and buildings of Tehran, it's the same symbolism really," Except that the Revolution's martyrs died "in the path of God," while Iron Maiden's die for nothing.A few of the bands in LeVine's book confront government and religious leaders directly through their lyrics. Most fear that becoming too "political" will result in even harsher oppression. But they all, on some level or another, are engaged in acts of culture jamming, taking the starkness and brutality imposed on them by others and making it their own. LeVine shows how heavy metal is the prefect engine for this sort of creative expression and how its creators won't be bullied into silence anytime soon.

LeVine has created a YouTube playlist featuring videos and concert footage from most of the bands he talks about in the book. Check it out.

Cross-posted on Kristopher's blog.

Monday, December 15, 2008

Explosive Excellence

I had intended to review The Chocolate War by Robert Cormier, but in compiling notes and a blurb, I Googled the book and saw that this may be the most reviewed YA book in the world. (I was assigned The Chocolate War during my high school freshmen year English class. I foolishly skipped reading it and watched the movie instead. I missed out on one of the great classic coming of age novels. I read it as an adult, and it’s a wicked beast of a story. I highly encourage you to read it.)

I had intended to review The Chocolate War by Robert Cormier, but in compiling notes and a blurb, I Googled the book and saw that this may be the most reviewed YA book in the world. (I was assigned The Chocolate War during my high school freshmen year English class. I foolishly skipped reading it and watched the movie instead. I missed out on one of the great classic coming of age novels. I read it as an adult, and it’s a wicked beast of a story. I highly encourage you to read it.)Instead of Cormier’s often mentioned classic, I have decided to offer for your consideration the most important book of fiction I have ever read. Ralph Waldo Ellison’s Invisible Man is sometimes included on must-read lists of English literature, but it’s more often forgotten. Like the book’s protagonist, this is a work of fiction that lives in the shadows of literature. When it emerges, it is powerful, shocking, and eloquent.

This isn’t a science fiction book. If you’re looking for a literally invisible man in this book, you won’t find one. The invisible man of science fiction resides in the H.G. Wells classic. The invisible man of Ellison’s book is figuratively invisible. He’s a black man living in America in the first half of the twentieth century. As the book’s prologue explains:

I am an invisible man. No, I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allen Poe; nor am I one of your Hollywood-movie ectoplasms. I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids—and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me.The plot begins with our narrator (who is never given a name) as a young man, soon to enter college, at his grandfather’s deathbed. The grandson is given advice on how to navigate a complex social world where his race constantly puts him at odds against whites. “I want you to overcome ‘em with yeses, undermine ‘em with grins, agree ‘em to death and destruction, let ‘em swoller you till they vomit or bust wide open.” This is a surprise to the young man and his family who didn’t imagine these words coming from the patriarch. It was dangerous advice in the Jim-Crow-era South. Our main character is a model citizen, a valedictorian, a striver. The advice would reverberate in his mind. His desire and ability to be careful and successful would slowly unravel.

We follow our narrator to college, and soon trouble finds him. He escapes to New York, a place very different from the South for blacks. Despite the new freedoms and signs of cultural renaissance, there are dangers and trials at every turn. It is amidst these new difficulties that the young man discovers that he is invisible. He tries to define himself and stand up for ideas that begin to emerge from facing the chaos, but he is constantly put down. What kind of man can emerge from this constant misfortune?

Invisible Man is a challenging book, with dense symbolism and complex themes, but it is by no means above the reach of a young adult reader. I read it during my senior year of high school, and I was absolutely absorbed. I’ve read it a number of times since, and each reading reveals new layers and brilliant details. Ellison aimed to produce a work of fiction that read like a Duke Ellington jazz piece—riffs on themes and rapid-fire solos—and what emerges from the explosive and lyrical prose is the kind of book that stirs the soul of the reader and American literature.

Ralph Ellison published one novel during his lifetime, Invisible Man, in 1952. It was met with positive reviews and won the National Book Award. In some ways, the success of Ellison’s first novel hobbled his writing career. Ellison had a distinguished career as a scholar, but the public eagerly waited for a novel. An early draft of Ellison's second novel was lost to a house fire. Friends and writers knew Ellison continued to work on a novel throughout his life, but the second novel from the first-rate mind never emerged. Juneteenth was published after his death, but it was not Ellison's final draft.

Ellison believed that the nature of art was to demonstrate excellence, to shed light where the shadow fell. Invisible Man is truly a work of excellence.

Friday, December 12, 2008

Who Watches . . . ?

e form on the map for mainstream readers (along with Spiegelman's Maus and Miller's Dark Knight Returns), and one of Time Magazine's 100 greatest novels of all time, there is very little I could put into a new light for you in the space I have here. On the other hand, Watching the Watchmen: The Definitive Companion to the Ultimate Graphic Novel (by Gibbons, Kidd and Essl) has plenty of new and interesting stuff to say about it. Since Dave Gibbons, the artist of the original comics, has opened up with stuff about its earliest conception and never-before-seen sketches and ideas, this is going to be about the most in-depth analysis of the work you're going to find, this side of sitting down for a cup of tea with Watchmen author Alan Moore. As he is notoriously unhappy with the idea of this Watchmen in particular, I wouldn't count on that happening any time soon. For my part, I will say this. In my own personal theory of the evolution of the super-hero (and the super-hero comic), Watchmen is one of the three comics that have defined the genre. Action Comics #1 (featuring the first appearance of Superman) invented the super-hero. Amazing Fantasy #15 (featuring the first appearance of Spider-Man) made the super-hero recognizably human and introduced the notion of metaphor into a genre that had been painfully literal up to that point. It also gave the super-hero a motto ("with great power comes great responsibility," don't you know). Like those two comics, Watchmen (originally published as twelve monthly issues), summed up all that had come before it and paved the way for everything that would come after it. It dragged the super-hero into a context so real it was a bit disturbing and gave its characters such layered (and dark) personalities that the world suddenly realized comics, as the saying goes, weren't just for kids anymore. It pushed the potential of the genre to such a level of sophistication that it is still one of the very few works that could actually be considered graphic literature.

e form on the map for mainstream readers (along with Spiegelman's Maus and Miller's Dark Knight Returns), and one of Time Magazine's 100 greatest novels of all time, there is very little I could put into a new light for you in the space I have here. On the other hand, Watching the Watchmen: The Definitive Companion to the Ultimate Graphic Novel (by Gibbons, Kidd and Essl) has plenty of new and interesting stuff to say about it. Since Dave Gibbons, the artist of the original comics, has opened up with stuff about its earliest conception and never-before-seen sketches and ideas, this is going to be about the most in-depth analysis of the work you're going to find, this side of sitting down for a cup of tea with Watchmen author Alan Moore. As he is notoriously unhappy with the idea of this Watchmen in particular, I wouldn't count on that happening any time soon. For my part, I will say this. In my own personal theory of the evolution of the super-hero (and the super-hero comic), Watchmen is one of the three comics that have defined the genre. Action Comics #1 (featuring the first appearance of Superman) invented the super-hero. Amazing Fantasy #15 (featuring the first appearance of Spider-Man) made the super-hero recognizably human and introduced the notion of metaphor into a genre that had been painfully literal up to that point. It also gave the super-hero a motto ("with great power comes great responsibility," don't you know). Like those two comics, Watchmen (originally published as twelve monthly issues), summed up all that had come before it and paved the way for everything that would come after it. It dragged the super-hero into a context so real it was a bit disturbing and gave its characters such layered (and dark) personalities that the world suddenly realized comics, as the saying goes, weren't just for kids anymore. It pushed the potential of the genre to such a level of sophistication that it is still one of the very few works that could actually be considered graphic literature.Now, if you're looking for something about super-heroes that's got depth and power but you maybe haven't heard of before, definitely hunt down a copy of the Golden Age (by Robinso

n and Smith), which is actually about the end of the Golden Age (Golden Age super-heroes, that is). As the Justice Society of America returns from World War II, they find a world that doesn't seem to need or want them anymore, and they each find their lives tumbling out of control in various ways without the mission of justice that has always guided them. So, while you've got Green Lantern trying to hold his business together and Hourman finally realizing that he's a drug addict, unable to quit popping the pills that grant him an hour of super power every day, you've also got the Manhunter -- homeless, hopeless and a little bit insane -- being pursued by a group of shadowy killers. Why? Because he's stumbled onto the secret of the world's newest, shiniest super-hero: Dynaman. Would you be surprised to learn that Dynaman, though rallying 1950's America behind him, has a very dark secret and an even darker agenda? Lemme tell ya, this thing is thrilling all the way through, but pretty much the entire last chapter, as all the plots come boiling together, features about the most spectacular battle I've ever seen in a comic book, as the heroes assemble one more time against the most powerful among them. Not everyone makes it into the Silver Age alive.

n and Smith), which is actually about the end of the Golden Age (Golden Age super-heroes, that is). As the Justice Society of America returns from World War II, they find a world that doesn't seem to need or want them anymore, and they each find their lives tumbling out of control in various ways without the mission of justice that has always guided them. So, while you've got Green Lantern trying to hold his business together and Hourman finally realizing that he's a drug addict, unable to quit popping the pills that grant him an hour of super power every day, you've also got the Manhunter -- homeless, hopeless and a little bit insane -- being pursued by a group of shadowy killers. Why? Because he's stumbled onto the secret of the world's newest, shiniest super-hero: Dynaman. Would you be surprised to learn that Dynaman, though rallying 1950's America behind him, has a very dark secret and an even darker agenda? Lemme tell ya, this thing is thrilling all the way through, but pretty much the entire last chapter, as all the plots come boiling together, features about the most spectacular battle I've ever seen in a comic book, as the heroes assemble one more time against the most powerful among them. Not everyone makes it into the Silver Age alive.So Watchmen and the Golden Age aren't the most uplifting super-hero books ever. Unless you consider great stories, excellent characterizations, evocative art and thrilling action uplifting, that is.

Thursday, December 11, 2008

Possibly the Best Book I've Read This Year

In All Over But the Shoutin', Rick Bragg writes of growing up dirt-poor in Alabama, near the Georgia state line. His father, a Korean War veteran with post-traumatic stress, abandoned the family and drank himself to death at the age of 41. Mrs. Bragg picked cotton, took in ironing, and received welfare as she raised three sons (A fourth died soon after birth.).

His junior year, Bragg was named sports editor of the school newspaper because noone else wanted it. He writes, "I had no way of knowing, then, that it would be my salvation."

After high school, he enrolled in a journalism class at the local university and started writing for a weekly newspaper. Bragg eventually won a Nieman Fellowship for journalists to Harvard University, and was a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter for The New York Times.

I've read about a hundred books this year, and this is the one I'm telling everybody about. Rick Bragg knows how to tell a story, and he has a bunch of good stories to tell. When I finished this one, I immediately started listening to a recording he made of his next book, Ava's Man. For that book, he gathered stories from people who knew his mother's father. It's very good, too.

Author Pat Conroy wrote, "Rick Bragg writes like a man on fire. And All Over But the Shoutin' is a work of art... I never met Rick Bragg in my life, but I called him up and told him he'd written a masterpiece, and I sent flowers to his mother." It is a masterpiece, and she deserved the flowers.

Wednesday, December 10, 2008

Death From the Skies!

You can't beat a title like that for a book, exclamation point and all.

Everything under this wave of sound was stomped flat. Trees that were ablaze a moment before from the heat of the explosion were snuffed out, then torn into millions of splinters. The expanding ring of pressure, already dozens of miles across, screamed past the location of Mark's disintegrated house and continued moving, greedily consuming buildings, trees, cars, people. Before it was over, the shock wave circled the Earth twice...

This is the scenario for a relatively small meteoroid slamming into Earth -- about seventy yards wide -- laid out by author and Philip Plait in his can't-look-away true-to-life collection of cosmic disaster scenarios, Death From the Skies. Subtitled These Are the Ways the World Will End, Plait focuses his Astronomer's eye on the types of dangers lurking within (and outside) our solar system and explains all the ways that the universe seems out to get us. There's space debris of all sizes, sun spots, gamma rays, supernovae, black holes, exploding stars... all the stuff of science fiction brought down to Earth in tidy, horrifying packages that are as entertaining to read as they are hard to believe. But it's all possible!

Spawned by the wave of sub-atomic particles, a thick layer of smog began to form in the air, and within days the sky was a dank reddish-brown color over the entire planet. Any hardy plant that had managed to stay alive thus far suddenly found the sunlight and temperature dropping... which was bad enough, until the acid rain began...

Plait lays out a scenario for each possible catastrophe, then backtracks and explains the science in great detail but in very approachable language. Then he includes real examples of known or observed phenomena that correlates with the particular subject at hand, and finishes off with the likelihood of it happening here on Earth. The most frightening aspect to all of this is that it's all pretty much out of our control. Astronomers observing massive sun spot activity and the resulting dangers for Earth would have barely eight minutes to respond and warn the public. And in that time nothing could be done to stop the destructive power that could cripple the entire power grid for half the planet in a matter of seconds anyway.

Just a few weeks after the first trouble began -- and its position still 300 million miles away -- the black hole's gravity as felt on Earth is equal to that of the Sun. Earth no longer orbits one star: it is enthralled by two: one living, one dead. Within a few more days, the black hole's influence is far stronger than the Sun's. Grasping the Earth with invisible fingers, it tears us away from the Sun, bringing us closer to the collapsed star. As we approach, the gravitational tides from the black hole begin to stretch the Earth...

Like a horror show or an accident where one can't help but steal a glance, Plait dangles the disaster like a carrot at the beginning of each chapter before calming us down with the rational, sometimes amusing, explanations. The likelihood of most of these things happening, not just in our lifetimes but ever, may be very slim. Plait's point is that the dangers are nonetheless out there, and if they're going to happen, this is what it would look like.

To any teen who's ever seen a movie or read a book where an asteroid is threatening to destroy the planet and wondered if it were possible, or doubted the science in such fictions, or really wanted to know what would happen when the Earth finds itself on a collision course with the powers of the universe, this is the book for them.

Honestly, I would have loved to have gotten this for Christmas when I was a teen. Instead I got Jonathan Livingston Seagull. 'Nuff said.

Death From the Skies

These Are the Ways the World Will End...

by Philip Plait, Ph.D

Viking 2008

Tuesday, December 9, 2008

'Twas the Night Before Christmas

It being December, I thought I'd talk about one of the most famous Christmas poems ever. Okay, if I'm honest, probably THE most famous. Its actual name is A Visit From Saint Nicholas, and it was written in the early 1800s. It has long been attributed to Clement Clarke Moore, a resident of New York who, I recently learned, just happened to be a slave owner, and was opposed to the abolitionist movement. There is evidence to suggest that the poem was not written by Moore, but was instead by Major Henry Livingston, Jr., one of his wife's relatives. But I digress.

It being December, I thought I'd talk about one of the most famous Christmas poems ever. Okay, if I'm honest, probably THE most famous. Its actual name is A Visit From Saint Nicholas, and it was written in the early 1800s. It has long been attributed to Clement Clarke Moore, a resident of New York who, I recently learned, just happened to be a slave owner, and was opposed to the abolitionist movement. There is evidence to suggest that the poem was not written by Moore, but was instead by Major Henry Livingston, Jr., one of his wife's relatives. But I digress. The poem is often called by the start of its first line; the poem begins as follows:

'T was the night before Christmas, when all through the house,

Not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse;

The stockings were hung by the chimney with care,

In hopes that St. Nicholas soon would be there;

The children were nestled all snug in their beds,

While visions of sugar plums danced in their heads,

And Mama in her 'kerchief, and I in my cap,

Had just settled our brains for a long winter's nap-

When out on the lawn there arose such a clatter,

I sprang from the bed to see what was the matter.

A version of the entire poem as it was originally printed can be found online. New books containing the poem come out nearly every year. The two you see here are two of my favorites in recent years, but there are truly versions for everyone.

A version of the entire poem as it was originally printed can be found online. New books containing the poem come out nearly every year. The two you see here are two of my favorites in recent years, but there are truly versions for everyone. But I don't just want to talk about the poem as it exists; I'd like to talk also about the many parodies this poem has inspired.

A parody poem is, as one might guess, a poem that is a parody (or send-up) of another existing poem. For instance, in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll includes a parody of "Twinkle, twinkle, little star", when he has the Mad Hatter recite the following (which he breaks off unfinished, lest you think I got lazy):

Twinkle, twinkle, little bat!

How I wonder what you're at!

Up above the world you fly,

Like a teatray in the sky.

Twinkle, twinkle—

Parodies of A Visit from St. Nicholas abound. There appear to be versions for nearly every fandom: there's a Star Trek (TNG) version, "Twas a Star Trek Christmas, a Dr. Who version, "The Night Before Christmas, on the Tardis, an homage to the work of H.P. Lovecraft, a NASCAR Christmas, a LOTR "Middle Earth" version, and more. In fact, some guy has put together a Canonical List of Twas the Night Before Christmas Parodies that should kick up something for nearly every interest - and then some.

The first line of the poem sparked not only the title of The Nightmare Before Christmas, but the original idea, which was a three-page poem written by Tim Burton based on A Visit from St. Nicholas, How the Grinch Stole Christmas, and Rudolph, the Red-Nosed Reindeer. It has also made its appearance in comics (including Garfield and Fox Trot), comix (issue 40 of DC Comic Young Justice was devoted to the poem, which involved Santa v. an alien, and the Winter-Een-Mas webcomix at CTRL+ALT+DEL), movies (including Die Hard and National Lampoon's Christmas Vacation), and television shows (including Friends, Animaniacs, and Danny Phantom). To say nothing of the parody The Night Santa Went Crazy by Weird Al Yankovic, animated by Nicklaus Liow.

The first line of the poem sparked not only the title of The Nightmare Before Christmas, but the original idea, which was a three-page poem written by Tim Burton based on A Visit from St. Nicholas, How the Grinch Stole Christmas, and Rudolph, the Red-Nosed Reindeer. It has also made its appearance in comics (including Garfield and Fox Trot), comix (issue 40 of DC Comic Young Justice was devoted to the poem, which involved Santa v. an alien, and the Winter-Een-Mas webcomix at CTRL+ALT+DEL), movies (including Die Hard and National Lampoon's Christmas Vacation), and television shows (including Friends, Animaniacs, and Danny Phantom). To say nothing of the parody The Night Santa Went Crazy by Weird Al Yankovic, animated by Nicklaus Liow.He sprang to his sleigh, to his team gave a whistle,

And away they all flew like the down of a thistle,

But I heard him exclaim, ere he drove out of sight,

“Happy Christmas to all, and to all a good-night.”

Monday, December 8, 2008

5 Quick Questions for Dennis Shull

Though Dennis is a teacher and librarian, I know him through his role as director extraordinaire of local church community theater productions. His interests are quite varied, as you will see below.

1. What do you do for a living and what do you like best about your job?

I'm a "retired" teacher, who spent 20 years teaching English, Speech & Drama, and Shop at the junior high level, then became a librarian and technology coordinator at the high school level for the last 10 years. At present, I still work for the same school district part-time, taking care of the adaptive technology needs for the blind and disabled kids in the district one day a week, and trouble-shooting technology needs at the district's new high school one other day. The rest of the week I work for a company that produces decorated sportswear, maintaining their line of sample garments, and manning the Help Desk for their sales representatives. As you might have guessed, I'm only content when my work environment is busy and varied. The thing I like best about my work is that every day is different, and each day usually brings a new challenge.

2. Besides for simple information, why do you read?

I love the seclusion and and introspection that reading allows... I delight in discovering a character who thinks and feels as I do, and then traveling down the literary road with him to further self-discovery...

And there's nothing more exiting than jumping on the magic carpet of imagination and following a complex character through a richly-textured adventure.

3. What did you read when you were a teen?

These are the names that come to mind, because at some point in my life, I read one book—and then wanted to read anything else by the same author:

Robert Heinlein

John Steinbeck

Mark Twain

Kurt Vonnegut

C.S. Lewis

And yet, the books that truly changed my life were often times one-hit wonders, like To Kill a Mockingbird, Watership Down, or Flowers for Algernon.

I also read a lot of comic books. ( I'm a firm believer that reading is reading: teens should read whatever level of literature appeals to them. They'll get to the "classics" when they're ready.)

If only these Young Adult authors had been available back in the Dark Ages when I was a teenager, I know I would have devoured every word they penned:

Robert Cormier

Chris Crutcher

Will Hobbs

Lois Lowry

Chris Lynch

Norma Fox Mazer

John Marsden

Gary Paulsen

Katherine Paterson

Philip Pullman

Cynthia Voigt

4. What book(s) do you wish you had read as a teen?

I really have no regrets. (See my "comic book" note above.)

5. What are you working on now?

It's been a dry spell. I've read lots of books in the past six months,but these are the only ones I'd recommend:

Our Story Begins, a new anthology of short stories by Tobias Wolff, Lush Life by Richard Price (dark, violent, and full of raw language), The Night Gardener by George Pelecanos (also dark, violent, and full of

raw language), Birds in Fall by Brad Kessler

Thank you, Dennis!

Friday, December 5, 2008

Dooley Takes the Fall -- Norah McClintock

Seventeen-year-old Ryan Dooley has been trying to walk the straight-and-narrow. His uncle's strictness chafes, but Ryan's been going to school regularly, avoiding drugs and alcohol, and generally just trying to stay out of trouble. He was on his way home from work at the video store when he found the body.

Seventeen-year-old Ryan Dooley has been trying to walk the straight-and-narrow. His uncle's strictness chafes, but Ryan's been going to school regularly, avoiding drugs and alcohol, and generally just trying to stay out of trouble. He was on his way home from work at the video store when he found the body."I thought I recognized him," Dooley said, which was true. "But his head was kind of smashed up, so I wasn't sure" which wasn't true, but it sounded a lot nicer than saying was he was actually thinking (It couldn't have happened to a more deserving person), which would only have annoyed his uncle. "Anyway, I didn't know that was his name and the cops didn't tell me," which was also true. He glanced at the picture in the newspaper and this time recognized the face right away--Mark Everley, his longish hair combed back, posed in front of one of those gray-blue screens that school photographers use, smiling at the camera, looking like your average high school student, which was a whole lot different from looking like a broken doll. The newspaper picture of Everley triggered another one in Dooley's mind, but this one wasn't from school. Dooley's dominant impression: Mark Everley was an asshole.

What with his past, it isn't long before Dooley becomes a prime suspect in what might be a murder investigation. And it isn't just the cops and his uncle who suspect him of having something to do with the death -- it's also Mark Everley's sister, a girl who Dooley's been curious about for ages.

Dooley Takes the Fall is fantastic. FANTASTIC. This isn't just a simple murder mystery. Dooley has that aspect of the story to deal with, but the reader has more: Dooley's past -- What He Did before coming to live with his uncle and his history with Mark Everley -- spools out slowly, and it, more than the actual mystery*, kept me entranced from the first page to the last. One of the real strengths of this book was the lack of expository dialogue -- I felt like Dooley and the other characters acted and spoke realistically throughout, never explaining things to each other just for the sake of explaining them to me. Norah McClintock has respect for the reader's intelligence, trusts the reader to be an active participant. I love that.

Dooley himself is a great character. He's a classic noir hero type -- troubled past, problems with addiction and unlucky in love, sometimes has a hard time getting out of his own way -- which I always find appealing. And he's got great taste in movies:

Dooley said he liked some of the British stuff better. "You mean, Guy Ritchie and what's-his-name, the guy who did The Limey?" Mr. Fielding had said. No, Dooley said. Some of the quieter stuff, the stuff they showed on TV there but that you could rent here. He said he liked Robbie Coltrane, the character he played, he drank too much, he ate too much, but he always figured out the case without breaking a sweat, and you know what? The guy didn't even own a gun. Yeah, Dooley liked him a lot.

He's talking about Cracker! Cracker, if you haven't watched it, is outstanding -- if I hadn't already been hoping that all would go well for Dooley by that point, that passage would have won me over. Speaking of hoping things would go well -- until the very end of the book, I really didn't know which way things would go. There was no element of predictability -- yet another thing I loved about the book.

Highly, highly recommended to people who are disappointed by the lack of crime novels in the YA section, to people who liked the movie Brick, and to people who like their mystery novels to be more than simple mysteries with quick quips and chases scenes, but stories with depth and heart. Dooley Takes the Fall is a crime novel, yes, but it's also a story about trust and redemption. I loved it unreservedly.

I am so grateful to the person who nominated this title for the Cybils. Up until now, Norah McClintock hadn't been on my radar. Now I'm planning on going back and reading her entire backlist while I wait for the second book in the Dooley trilogy to appear.

(cross-posted at Bookshelves of Doom)

_________________________________________________________

*That said, the mystery was strong, too.

Thursday, December 4, 2008

Now we are blaming the fathers

I'm not making this up, and here's the proof:

Boys loved being read to when they were tots. Now, as teens, they still like somebody reading to them. But somewhere between third and fifth grade, there was a disconnect between boys and books. Aha! Isn’t that when gender consciousness bursts into full flower? When the lines are drawn between the sexes? Sure, before then, in the schoolyard, boys played with boys and girls with girls. But back at home, in the neighborhood, things were different: young boys and girls still played together. In fact, some were best friends. But by the time boys hit third grade, those who played with girls became the butt of other guys’ jokes. So instead, they did boy things—and reading wasn’t one of them.

Someone's going to have to tell me just what that magic button is that gets pushed in the third grade because I bet a lot of parents would like to dodge that "girls bad" bullet.

Here's the other fun part:

Moms frequently read to their young sons at bedtime. Elementary school teachers and media specialists, who are primarily women, read to their classes. And in movies and on TV, it’s women or girls who are typically rushing off to their book clubs. Men don’t read—instead, they do. For instance, men don’t read books about hunting, they hunt. They don’t devour novels about race-car driving; they go to drag races—and often take along their sons. For many boys, reading becomes a chore that prevents them from pursuing manly things, like playing sports, fishing, rock climbing, and, later, chasing girls. Testosterone keeps guys running and gunning, and if they don’t see members of their own tribe reading—trust me—they won’t deem it important.

Leaving aside the cliches about what men and women like that are thrown out in this paragraph, (Okay I can't leave them alone - men hunt and race cars while women read books? Did Sarah Palin leaning over that bloody moose carcass and the ten zillion pictures of Barack Obama with a book in his hand show us anything about modern gender roles at all??) This argument - and lord knows we have all heard it before - does not work for me because if it was true there would be thousands (and thousands) of more female writers in this country then male. Men would not grow up reading and thus they would not pursue writing careers. And yet, we know that is not true. This makes me wonder then where all the male writers come from in America. (Europe? Canada? Are they secreted across the borders at the age of 18?)

Also, why - FOR THE LOVE OF GOD WHY - do people feel so comfortable making huge sweeping statements like this? In my house my father read as much as my mother (if not more according to my brother) and my brother is still a voracious reader. All the guys at the comic shop I frequent are just that, guys. I worked with guys at the bookstore in Fairbanks, I went to grad school with many many guys (all of whom had to read tons of books just to stay in there) and most of my teachers in college were - wait for it - guys.

Men read. Can we just acknowledge this once and for all? Men read.

Having written all that, yes I do know that girls seem to read more than boys in the teenage years. There are studies and I did read them and part of that was why Guys Lit Wire was created in the first place - to find a way to get teenage boys reading more. However, I have a critical difference of opinion with this article. I do not think that boys (or girls) read or don't read because of what other people do (or don't do) in their homes. My parents, as I mentioned above, were huge readers but they each came from parents who never read anything when they were growing up beyond the local newspaper (and even that was not a given). So why did they become huge readers? Who knows - but they did. And they aren't the only kids who grew up in houses without reading parents who still managed to crack open a book.

Should we encourage more teenage boys to read? Yes - in any way, shape or form (and that includes comics) just as we should encourage teenage girls. But blaming it on the parents this way? Saying one reads too much to their kids and one reads too little? How does that help exactly? Why not just suggest taking the kids to the bookstore for a treat? (My parents did that.) Or taking them to the library and letting them get whatever they want (and hanging out perusing the books yourself and waiting for them and making it a family thing)? (My parents did that too.) Or letting them grab an Archie comic at the check out stand? (Yep - my folks again.)

You don't have to be a reader to raise one, you just have to be an interested parent who encourages your kid to read. And you know what else? I graduated from high school with a close friend I made in the first grade - and one from the second - and several from the seventh and the eighth and all of them, a dozen or more, were boys. Some of them were readers and some weren't but all of us managed to still enjoy going out for pizza, watching movies and hitting the beach to surf in spite of the fact that we weren't the same gender.

Will wonders never cease?

He Said, She Said- Soulless by Christopher Golden

Welcome to He Said, She Said, a feature for GuysLitWire in which a guy (Book Chic, a recent college graduate) and a gal (Little Willow, a bookseller), discuss books that will appeal to both genders.

In October, we talked about Poison Ink (link) by Christopher Golden. Then LW got BC to read Soulless, Golden's newest YA novel. We're both crazy about this spine-tingling zombie tale.

Times Square, New York City: The first ever mass séance is broadcasting live on the Sunrise morning show. If it works, the spirits of the departed on the other side will have a brief window -- just a few minutes -- to send a final message to their grieving loved ones.

Clasping hands in an impenetrable grip, three mediums call to their spirit guides as the audience looks on in breathless anticipation. The mediums slump over, slackjawed -- catatonic. And in cemeteries surrounding Manhattan, fragments of old corpses dig themselves out of the ground....

The spirits have returned. The dead are walking. They will seek out those who loved them in life, those they left behind...but they are savage and they are hungry. They are no longer your mother or father, your brother or sister, your best friend or lover.

The horror spreads quickly, droves of the ravenous dead seeking out the living -- shredding flesh from bone, feeding. But a disparate group of unlikely heroes -- two headstrong college rivals, a troubled gang member, a teenage pop star and her bodyguard -- is making its way to the center of the nightmare, fighting to protect their loved ones, fighting for their lives, and fighting to end the madness.

LW: It's true - The dead travel fast. The book was extremely fast-paced, and I whipped right through it. Total page-turner.

BC: I agree with Little Willow. While I wasn’t enamored with Golden’s prose in his other teen book this year, Poison Ink, I really enjoyed this one and can see why LW loves Golden so much!

LW: While I enjoyed Poison Ink, I also loved Soulless.

Do you like zombie stories (books, movies, etc) as a general rule?

LW: I like well-written horror stories and ghost stories, and thus I can enjoy well-told zombie stories, but I don't actively seek them out. Though I haven't seen any of the staple zombie films, I think this book would make an excellent film.

BC: Generally, no. Anything remotely horror I completely avoid. I’m very easily scared and then I’m up all night and I don’t get sleep and then I can’t go job hunting because I look like a zombie and I’ll frighten off prospective employers. And that’s not good.

Why did you get this book?

LW: I read anything and everything written by Christopher Golden. The man truly has the Golden touch. He writes intriguing, inventive stories, and he's a great storyteller. In Soulless, he effortlessly balanced everyone's backstories and plotlines, then wove them together tightly.

BC: I got this book firstly because the cover and synopsis intrigued me. I know I said that I avoid horror-type stuff, but what can I say? I can be a masochist sometimes. I’d heard about it earlier this year and wanted to get a copy of it at some point. Secondly, LW really wanted me to read Golden (actually, I’m not really that special; she wants everyone to read Golden, not just me).

(LW starts cracking up, then nods enthusiastically.)

LW: It's true - There's a Golden book for everyone! Okay, continue.

BC: I had gotten Poison Ink randomly in the mail and figured that would be a good start. Once I finished that, she helped me get in touch with Christopher so that I could get a review copy of Soulless.

What did you think of the cover?

LW: I think it's gorgeous. Quite eye-catching. I know the eye on the cover is dominant, but I swear that I didn't intend the pun! I'm just going to go stare at the cover some more now . . .

BC: Ha ha, puns rock!

LW: Yes, yes, they do.

BC: I love the cover and it’s quite honestly the first thing that drew me to the book. I saw it somewhere (maybe on Cynthia Leitich Smith’s blog?) and was like “WOAH. Me. Want. Now.” See, when I notice a book with a REALLY good cover, I tend to lose that whole sentence-forming part of my brain and I become very similar to a caveman.

LW: I researched the tagline and discovered that "the dead travel fast" was used in Dracula, and, subsequently, various films inspired by or related to the book. Apparently, Bram Stoker was inspired by a folk ballad by Gottfried August Burger entitled Lenora, or Lenore, in which it is said (or sung) that "the dead ride quick." Stoker used "the dead travel fast" again in Dracula's Guest. The internet has provided me with the following phrases in other languages:

Denn die Todten reiten schnell. - from the novel Dracula

Pentru că morţii umblă repede! - from the 1992 film version of Dracula

BC: Wow, that’s really interesting! I didn’t know that at all. I learn something new every day, despite being out of school.

Soulless had a big cast. Who was your favorite character?

LW: Tania, the pop star, was my favorite main character. Derek, her bodyguard, was my favorite supporting character. I liked all of the main characters. Each brought a different flavor to the table. I liked how diverse the cast was, and I liked that each person and plotline was important.

BC: I gotta agree with Little Willow - I really enjoyed Tania too (who, by the way, has the same name as the pop star in the Heather Wells mystery series by Meg Cabot; I’ve never seen that name before and then, wham! It's in two different books, but both are pop stars) but that's kinda because I really enjoy reading about pop stars, even though her fame had little to do with her story. But I really enjoyed all the characters; like LW said, each was different and unique, so you had something to look forward to in each section.

Have you ever participated in a séance? If not, would you? Do you believe that mediums can communicate with ghosts?

LW: I have never participated in a séance or spoken to any clairvoyants. I'd have to be a part of a séance or a discussion with a medium to believe it myself. In other words, I couldn't just be an audience member or a bystander, because I wouldn't know if they (the mediums and/or their living 'clients,' if you will) were speaking the truth.

BC: I have not participated in a séance before, unless I’m blocking it out because of how scary or traumatizing it was. I’m not sure if I ever would participate in one, but I’m learning toward ‘no’. As for the belief, I guess anything’s possible, but I don’t think mediums can communicate with ghosts. I could be wrong though, as it’s not like I’ve done much thought or research about it.

LW: I've read many, many books and seen many, many TV shows and films that include ghosts and psychics. I enjoy The Ghost and Mrs. Muir by R.A. Dick (both the book and the film), The Ghost Wore Gray by Bruce Coville, The Doll in the Garden by Mary Downing Hahn -- Oh, stop me before I name a dozen things! Anyhow, I was a huge fan of The Dead Zone television series (not so much the film, and I haven't read the book), in which the main character, Johnny Smith, was psychic. I loved how Johnny (Anthony Michael Hall) spoke with and saw people, dead or alive. He had such a gentle way about him and conveyed such empathy. I rather think that he would have worked well with Phoenix's dad.

Are you spooked by the idea of ghosts or zombies?

LW: I'm not. If I met a zombie and he or she attempted to harm me, I'd certainly fight back and kindly ask that my brains not be eaten. I'd like to think my cats are still hanging around, walking beside me, and that I'm making my ancestors proud. My grandfather passed away a decade before I was born; I would have liked to have known him.

BC: Very much so. As mentioned earlier, I’m easily spooked by a lot of things. So, in my daily life, I try to avoid thoughts about ghosts, zombies, bogeymen, etc. because otherwise it’s hard for me to fall asleep or walk around without lights on.

If there were a sequel, would you read it?

LW: In a heartbeat.

BC: Totally.

Visit the SOULLESS website:

http://www.christophergolden.com/soulless/

Little Willow's review of SOULLESS:

http://slayground.livejournal.com/412431.html

Book Chic's review of SOULLESS:

http://guyslitwire.blogspot.com/2008/11/book-review-soulless-by-christopher.html