I have to give author Melissa Wyatt a lot of credit for setting her coming-of-age drama, Funny How Things Change, in West Virginia. The butt of thousands of late night jokes, the state is known more for what everyone says about it then anything else. Wyatt counters these misconceptions head-on with her story about high school grad Remy who is conflicted about his girlfriend's plan to leave their hometown of Dwyer for Pennsylvania where she intends to go to college and he plans to live with her. He thinks it is an okay plan but more importantly, he knows he is supposed to think it is a good plan. The problem is that the more Lisa talks about what she wants, the more Remy begins to consider how what he wants doesn't seem to be much of a concern for her - and the more he begins to realize that he doesn't really know what he wants anyway. That's a big problem when you're thinking about leaving home to be with someone forever and it's even worse when that someone doesn't seem to know (or care about) what you want either.

Here's a bit of what Remy is going through with his girlfriend Lisa:

Remy stood, his hands jammed into his back pockets, and looked out over Dwyer. Everything was going wrong. It wasn't supposed to be about sacrifices, but about doing what they wanted, both of them.

"I don't know." He couldn't trust himself to say any more.

"Oh!" Lisa got to her feet. "What does it matter what you do? It's not like working in a garage is a career or something!"

It was another sucker punch, only he knew she wasn't deliberately taking a jab at him. It was how she saw things. He stared at her, feeling like he'd swallowed his own heart, and wondered why she still looked the same when it felt like he was seeing her in a whole new way.

I saw a quote the other day from the current president of the United Steelworkers Union. He said that Washington has two sets of rules, one for those who shower after work and one for those who shower before. That classism - the notion that those who actually get dirty to earn a living with their hands are somehow less intelligent, less creative, less significant, is just one of the many cultural constructs that Wyatt tackles with Funny How Things Change. (No worries about this degrading into stupid elitism/"Real America" vs the East Coast political campaign garbage though - it's just a straightforward peek at misconceptions.) Do you really have to go to college to be successful? Do you have to leave home to be happy? What makes a life worth living and what if your ideas are different from everyone elses? What should you do?

What would you do?

Funny How Things Change is a revelation in many ways and a book I highly - highly - recommend. Remy is a very engaging and relatable protagonist, the problems and concerns for people in small town WV are explored (like mountaintop mining)and there's also a nifty subplot with a female artist who has been hired to paint murals on water towers across the state.

We do not live in a "one size fits all world" and it is wrong to think that we should all pursue one type of success. Remy is brave enough to stop and consider just who he wants to be before he is swept away by the expectations of others. He is a wonderful character and this is a very cool book.

Funny How Things Change will be released on April 27th. Be sure to keep your eyes peeled for the Summer Blog Blast Tour announcement in May when I will be interviewing Melissa Wyatt at my blog, Chasing Ray.

[Post pic - what mountaintop removal looks like.]

October 1957, the USSR launched Sputnik 1, the first human-made object to orbit Earth. The 183 pound satellite, just a winking dot in the sky, terrified Americans, who realized they were behind the Russians scientifically.

October 1957, the USSR launched Sputnik 1, the first human-made object to orbit Earth. The 183 pound satellite, just a winking dot in the sky, terrified Americans, who realized they were behind the Russians scientifically.  Rocket Boys is, as much as anything, a love note to science, to the joy of learning stuff. Hickam reports on each successive launch attempt, from the materials tried to the equations needed to calculate their altitude. Through the books, he shows his rockets' evolution from crude pipe-bombs to truly amazing things soaring thousands of feet into the air.

Rocket Boys is, as much as anything, a love note to science, to the joy of learning stuff. Hickam reports on each successive launch attempt, from the materials tried to the equations needed to calculate their altitude. Through the books, he shows his rockets' evolution from crude pipe-bombs to truly amazing things soaring thousands of feet into the air.

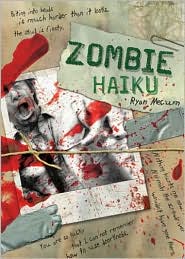

ZOMBIE HAIKU by Ryan Mecum tells the story of a zombie plague. It is presented as a journal full of poetry by some guy. At first, he's just a guy writing haiku (a lot of which are parodies of other people's poems, including those of Robert Frost and William Butler Yeats), but he continues to write haiku as he becomes a zombie and starts hunting for brains. However, right at the start, in the margins around the poems, there's some blue handwriting by a human guy who has been bitten by a zombie, but has grabbed the journal. So he sets up the scene (zombie plague, some people hiding out at the airport, all of them dying one way or another), and then he gets out of the way so you can read the story of the zombie plague straight through. The note-making guy comes back in at the end, with rather tragi-comic consequences.

ZOMBIE HAIKU by Ryan Mecum tells the story of a zombie plague. It is presented as a journal full of poetry by some guy. At first, he's just a guy writing haiku (a lot of which are parodies of other people's poems, including those of Robert Frost and William Butler Yeats), but he continues to write haiku as he becomes a zombie and starts hunting for brains. However, right at the start, in the margins around the poems, there's some blue handwriting by a human guy who has been bitten by a zombie, but has grabbed the journal. So he sets up the scene (zombie plague, some people hiding out at the airport, all of them dying one way or another), and then he gets out of the way so you can read the story of the zombie plague straight through. The note-making guy comes back in at the end, with rather tragi-comic consequences.