There are few topics more universal than family secrets. Every family has them, ranging from the tragic and devastating to pedestrian and silly. We cover up family secrets because we are often taught we must do so, but most of us can not look away from them or deny an interest to know more about how those secrets came to be. (The immortal heroine of a certain novel wasn’t called “Harriet the Spy” for nothing.)

Traditionally, literary teen detectives find their earliest genesis close to home, cracking open the mysteries of family and friends before embarking on those in the wider world. These stories are often relatable on a level that far flung adventures and dystopian dramas struggle to achieve. After all, while we all might love the idea of saving the world, ferreting out the lies that lurk around our own kitchen tables is something far more achievable.

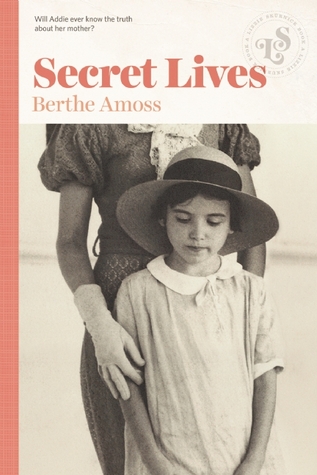

The titles Secret Lives by Berthe Amoss and Girl in Reverse by Barbara Stuber center on questions surrounding the life and loss of parents, especially mothers. In these historical novels, the protagonists suffer from feelings of abandonment and when tantalizing clues about their mothers are discovered they each embark on the hunt for more information.

By placing their characters far from the era of computers and cellphones, the authors allow their narratives to unfold slowly and carefully. With their climbs into attics and visits to cemeteries, Secret Lives and Girl in Reverse mimic the classic girl detective plots but there are no Scooby Gang moments of catching a nefarious villain. These books are all about finding answers to very personal questions and the delicate balance the protagonists must consider as they pursue their own pasts.

Girl in Reverse is the story of Lily Firestone, who was left at an orphanage by her mother when she was just a toddler. Now sixteen, she is the Asian daughter of adoptive Caucasian parents in 1951 Kansas. With the country immersed in the Korean War, Lily is frequently subjected to the cruelties of racism by her classmates and though dearly loved by her family, she is terribly unhappy. Everything changes when her younger brother Ralph finds a small box in the attic that came with her from the orphanage and includes a collection of Asian artifacts. Looking for information about the objects, Lily visits the local museum with its Asian exhibit, meets some of the archaeologists involved and eventually discovers what her birth mother had to hide and why. Surprisingly, Lily finds herself confronting someone she never expected and learns things that challenge her entire identity.

The Firestone family is unaware of Lily’s past and more importantly, have a great deal invested in leaving it alone. Her adoptive parents are living their post-war 1950s ideal of peace and prosperity and are steadfastly determined not to acknowledge any conflicts that Lily’s ethnicity might cause. They care deeply for their daughter, but Stuber does a fine job of showing how their love is not enough to change what people think about her and denying her difficulties serves only to exaggerate them. Lily is suffering and her family history is what she needs to uncover so she can feel secure. In her case, the questions are beyond her parents’ comprehension and thus all of her detective work must be conducted in secret, albeit with the delightful assistance of her brother, who grasps what their parents can not.

In Secret Lives, an out-of-print rerelease in the Lizzie Skurnick Books series, twelve-year-old Addie lives with her older unmarried aunts in 1930s New Orleans. Cared for by them since her parents were killed in a Caribbean hurricane, Addie is chafing at life in the genteel household and desperate to retain her fading memories of her mother. With the help of a new friend, who eagerly embraces the mystery, Addie finds her own puzzling clue in the attic, (proving it’s an old trope but a good one), and starts asking questions. In her case though, the truth is revealed more by listening and noticing—by gauging the reactions of others when her mother’s name comes up. Step-by-step Addie moves from one family member and friend to the next, pressing each for a bit more information until the final picture, the true picture, of her mother is revealed.

By the final pages of these two novels, each of the protagonists learns something about themselves and, more importantly, the people they love. These are predictable endings perhaps, in that the mysteries are solved and relationships affected for the better, but that does nothing to reduce their enjoyment. Collectively, we all love a good mystery and everyone of us has a relative who seems to be hiding something. Secret Lives and Girl in Reverse are proof positive that readers need not look far and wide for drama; all too often it is right beyond their bedroom doors.

No comments :

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.