Most lives take multiple chapters to get where they’re going. And just because there’s a pistol on the wall in the first chapter, nobody ever really knows if they’ll pull the trigger or catch the bullet by the third.

Most lives take multiple chapters to get where they’re going. And just because there’s a pistol on the wall in the first chapter, nobody ever really knows if they’ll pull the trigger or catch the bullet by the third.For instance, when I was a teenager thinking about who I’d be when I was 30, I pretty much assumed I’d be a famous (maybe infamous) writer by now. Or at the very least a rich one. I didn’t think that, while my two novels languished on the mid-list, I’d be working 12-hour shifts at a psych hospital. I certainly didn’t expect to find a writing program down here at rock bottom, or that it would teach me more about the value of art than my own literary ambitions could.

One of the first things a person discovers when they start working at a psych hospital is how many of their friends and friends of friends have stayed in a psych hospital. Like me, most of my patients didn’t expected to wind up here. Most of them won’t talk about it after they leave. It becomes a passing-through place, a point between there and there but never exactly “here.” For most people, it’s not a chapter in their lives but the blank space between one chapter ending and another beginning. It’s a long stretch of empty time to figure out how they got to this point and where they’re heading.

At least those are the things Robert tries to get the adolescents thinking about in his writing class. A drug addict turned drug councilor turned preacher who got his MFA last fall, Robert knows a little about writing and a lot about starting new chapters. Monday through Wednesday, he brings the adolescents into the classroom. They each pick one of the pictures taped to the whiteboard and write a story based it.

Every Thursday, Robert throws a book party, where the kids read what they’ve written in front of an audience. For confidentiality reasons, nobody can come except hospital staff. (The cleaning crew are the kids’ biggest fans.) Robert gets whatever drinks and snacks he can scrounge, and the kids pass out little handmade books with their stories in them. Then, one by one, they stand up and read about their dreams and pain, what they’ve seen and where they want to go from here.

Writing anything deeper than a grocery list means putting something of yourself on the page. It takes guts from anyone. And some of the kids that come here, the ones that have been abused, the ones involved in gangs or with parents in jail, have learned that opening up like that doesn’t bring anything but more hurt. A bad attitude makes good armor, and the toughest, snarliest kids, arms smeared with homemade tattoos, turn pale and shaky at the thought of dropping it.

Robert’s rule is simple: If they refuse to write, they go to isolation. Isolation is an empty ten-foot by ten-foot room with blank white walls. One kid, LaThomas, spent two afternoons in there. He’d come to the hospital after threatening teachers. He was already on probation for selling drugs and had a history of abuse and neglect. For two days, he sat on the floor in of that little room, trying hard to look menacing.

Finally he gave in. Maybe anything was better than the boredom of isolation, maybe he trusted us and the other patients by then. Whatever happened, he pulled a picture of a lion off the whiteboard and said he’d give it a shot.

Kids with ADHD tend to be visually oriented, which is why Robert settled on the picture-prompts. All the images have a scenario written on the back. They’re designed to make the kids make choices while writing their story. The back of LaThomas’ lion picture talked about being pushed into a lion’s pit and finding out she had cubs. From that, after a little more moaning and stalling, LaThomas managed to come up with this...

When I fell into the lion’s pit the lion had just had cubs. She couldn’t really take care of them. If Jim hadn’t pushed me down here, I wonder what would’ve happened. Would someone come in and save them? But it was me, so it was my problem.

Problem now, so I think about what I’m going to do, so it finally came to me. I grab a very thick vine that hung from the outside. I think it’s still on a tree. So as I climb up, I ran back to my car, go to the grocery store and ran in and grab some bloody pork chops. I go back to where the lion and her cubs. They look so hungry so I just feed them all the time.

Think about the kid who wrote it, and how easy it would have been for him to turn the story toward violence. Instead he talked about caring and taking responsibility. He let us see something vulnerable beneath the thug. In the face of all the crap I deal with in this job, I can’t help but feel a tiny bit privileged at that.

Dana was another patient that spent plenty of time in isolation. Once after sneaking a boy into her bedroom and then again after she distracted staff while a Romeo-and-Juliet couple jumped the fence and tried to run away. Dana was oppositional and sneaky. She hated anybody who told her what to do and would try to break the rules just to prove she could.

Because of her attitude, she wound up stuck here for twice as long as average. She watched the other patients she’d become friends with get discharged and head back to their real lives. Then her boyfriend at school hooked up with some other girl. Finally, something clicked. Dana realized she wasn’t wasn’t going anywhere until the doctor said she was. She started following the program, grudgingly, and mostly just to get out of her, but she started following it.

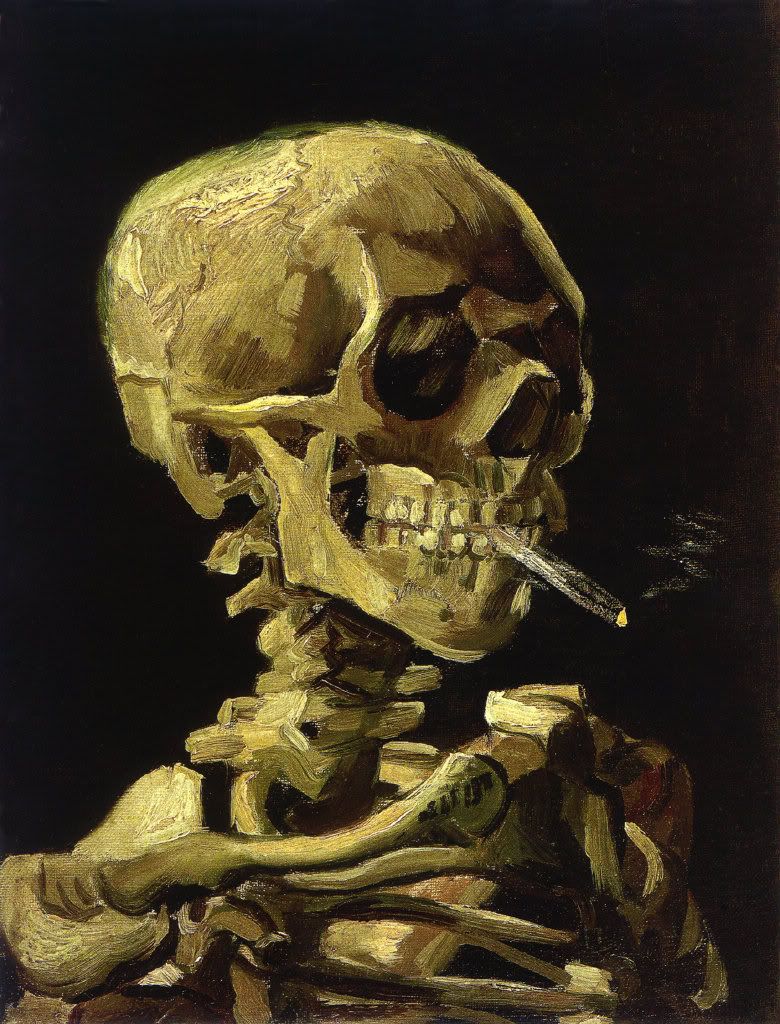

On her last day at the hospital, Dana got up and read a story inspired by a Van Gogh of a skeleton smoking a cigarette. She had to tell a story about the man and explain why he died, Dana turned it into about her father, herself, and even us that was so brutally honest I doubt many adults could manage it.

The man in this picture is what’s left of my father. Whether he died of a broken heart or of the lung cancer that the doctor diagnosed him of, I’m not sure. Maybe a combination of the two. But none the less, he’s gone and has been gone for over a year and a half. And I miss him. My father was my everything; my tear stopper, my secret keeper, my best friend. He lived forty-eight years, fourteen of them shared with me; but not near long enough. I think I’m losing it. It’s not the same anymore, and it never will be. Now I often hold things back, act like I’m okay. I’m not sure what emotions are right to fake anymore. Should I laugh or cry or maybe even smile.

My mother and I left one morning when my father wasn’t home; little did I know at the age of five that I wasn’t coming back. After many custody battles, I stayed with my mom during the week, and my father on the weekends. My dad smoked pretty much his whole life, and this is where the still lit cigarette comes into play. My father and I did everything together, but by the Christmas of my fourteenth year it all changed. I celebrated Christmas alone. He stopped doing things and slept most of the time. Little did I know that something far worse was going to happen.

By the next month, my dad was in the hospital and diagnosed with cancer. And within the next two months, my father died. He won’t see me graduate, and he won’t walk me down the aisle. His last words to me were that he loved me, and I know he did. But his love for me wasn’t enough for him to overcome his addiction. The cigarette is still lit, and my father isn’t coming back.

My doctor here in the hospital said I was superficial. I’m not trying to be superficial, but I just don’t understand how I am supposed to react to losing my father. I just feel numb.

Next time you think about lighting up, think about the people that love you: your family, your friends, your wife or husband, your boyfriend or girlfriend. Think of them all, and ask yourself if you are ready to take yourself from them. Or do you even care? For once, think about someone besides yourself and ask if they deserve what might be given to them. Do they deserve to lose you? Do you deserve to lose your life to something that could be prevented?

I myself at fourteen years of age was not anywhere close to being ready to lose my father, but maybe I’m being selfish. You can’t make decisions for other people, or my father would still be here. You can make decisions for yourself and your life and the people that you include in it. But when you make a choice, remember that it is not only you that is affected. That’s all I ask of you all, is just to think.

You have to understand that after a month of causing trouble, the staff really just did not like Dana. Everybody was more than ready to get her out of there. Despite that, after she finished reading and sat down, nobody clapped for several seconds, nobody spoke. She’s the only patient I’ve seen bring the audience to dead silence.

I don’t know where Dana or LaThomas or most of the kids go after they leave the hospital. I don’t really know where I’ll go once I leave. But I save each of the books they make every week. They crowd my shelf beside Huck Finn, Yossarian, and Randal Patrick McMurphy--all the voices shouting against madness and disappointment--because anybody going through the struggle of starting a new chapter deserves some small act of rememberance, a nod of respect.

X-posted on Kristopher's blog.

I taught school at a detention facility, and this brings back a lot of memories. Thanks for posting.

ReplyDeleteWow. Like Dana's audience, I needed a few seconds of silence.

ReplyDeleteHey, that was really moving. Thanks for sharing. I agree with you that "respecting" the journeys and words of Teenagers is HUGE!

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete